John Carpenter’s “Planaria”: or, The New Individualism

Sometimes you run into a concept that completely rewires your outlook.

It happened for me back in the eighties, when I encountered the definition of “Life” in Dawkins’ The Blind Watchmaker: “Information, shaped by natural selection”. That concise distillation—an actual description of what life is, as opposed to all those tired and exception-prone checklists that only talk about what life does— told me that you didn’t have to be squishy to be alive, you didn’t even have to have physical substance. It told me that carbon and silicon were just platforms, that a piece of software could be not just metaphorically but literally alive under the right circumstances. That single insight informed half a trilogy.

It happened again back in 2008 when I encountered Pepper et al’s paper on Somatic Evolution, a paper that posed a question mindbogglingly obvious in hindsight, but which had never occurred to me: how can multicellular life evolve in the presence of Darwinian processes that should, by rights, turn every individual cell against its neighbors in a competition for resources? Why isn’t every somatic cell in it for themselves, why doesn’t all multicellular life devolve into cancer? That particular question ultimately gave you “The Things”. You’re welcome.

And now, once again: a bolt from the blue that (for me at least) redefines the word “individual” in a way that could almost be a deliberate response to Pepper et al. An individual— an organism— is

“a living system maintaining both a higher level of internal cooperation and a lower level of internal conflict than either its components or any larger systems of which it is a component.”

What we have here is a definition that not only acknowledges the issue of cellular competition within the individual, but which is actually based upon it.

Here’s a corollary, which elevates us from the perspective of the individual to the shaping of entire populations:

“The major evolutionary transitions, including those from prokaryotes to eukaryotes and from free-living cells to multicellularity, all increase the scale over which cooperative interactions dominate competitive interactions.”

Personally I think that’s a bit clunky: I’d have just said symbiosis increases with complexity; antagonism diminishes[1]. However you put it, it provides an evolutionary rationale for the emergence of hive minds: competition waning between individuals the same way it did between cells, cooperation waxing, as individuals fuse to become a single superorganism. Put it that way and hive minds seem almost an inevitable next step, on the off chance that extinction doesn’t happen first.

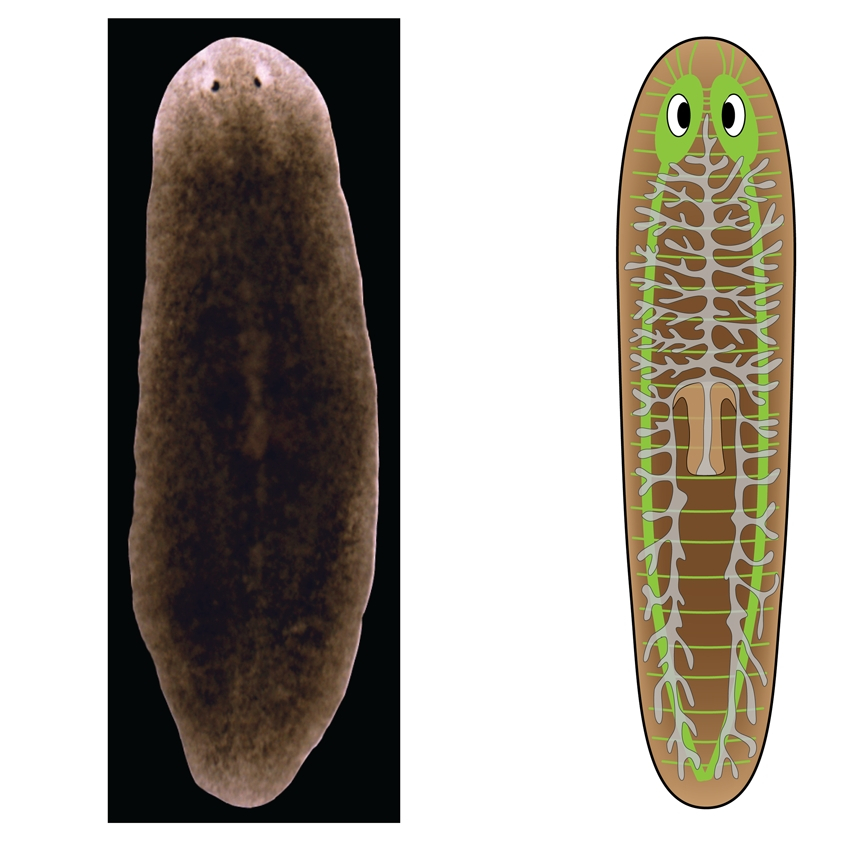

I found those little gems of insight quoted in a 2018 paper from Fields and Levin. They weren’t talking about hive minds, of course. They were talking about something far more down to earth: those humble, endearingly cross-eyed little flatworms everybody learns about in first-year biology. You know: Planarians. Dugesia et al.

Except, if this paper is right, they’re not exactly worms. They’re not even individuals. What they are is habitats: cellular substrates containing individuals. Individuals who may not even like each other very much.

There are these things called neoblasts—stem cells, basically. They only comprise about 20% of any given planaria, but they’re the ones that keep the whole worm running. A single neoblast can build an entire worm from scratch; they not only produce new neoblasts but they also give rise to the other cells that comprise the remaining eighty percent of the body. Those guys don’t even divide; they’re perennially post-mitotic, they just kind of sit there being muscle fibers or digestive cells or neuroconductors for a week or so before dying off. (Fields and Levin compare them to the sterile workers in insect hives; the queens in that scenario being, of course, the neoblasts themselves.)

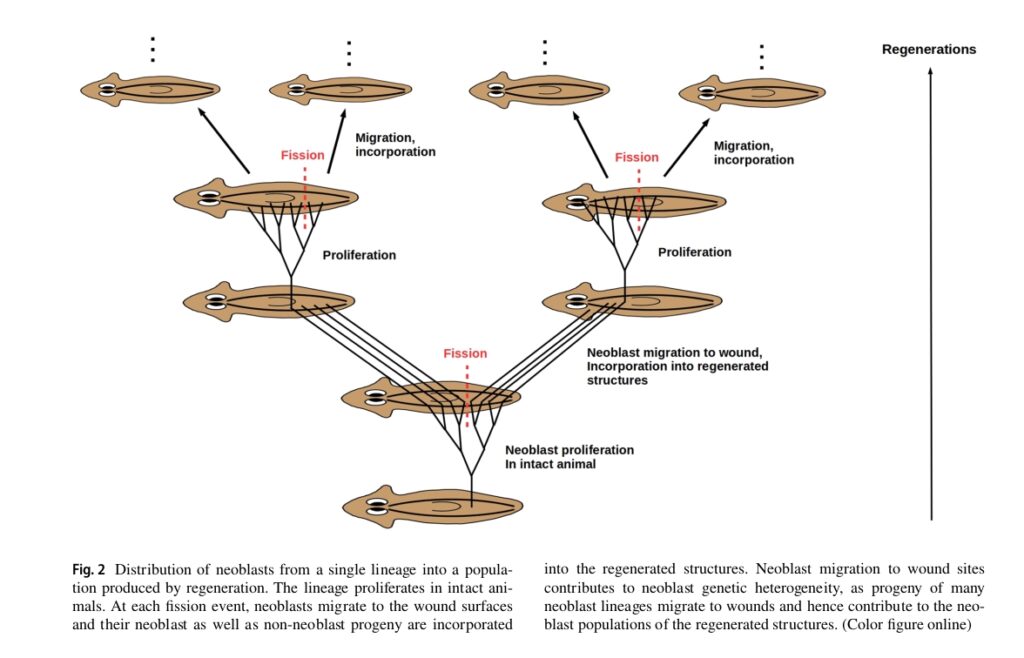

Also—and this is especially wild—genetically-different neoblast lineages can be found in the same planarian body. Turns out the genes tend to mix it up at wound sites: neoblasts and non-neoblasts exchange genes during wound repair, which changes the gene frequencies (not to mention sharing any mutations which have turned up along the way), effectively forging new lineages. Further, asexual reproduction in planaria is a form of self-inflicted wounding: the worm literally rips itself in two, each piece subsequently regenerating into a whole worm. So neoblast lineages diverge, both during reproduction and repair. You end up with gangs of neoblasts—tribes, if you will—whose members are bound to each other by genetic similarity and put at competitive odds with less-similar neoblast populations living in the same body.

I’ve been focusing on asexual reproduction, but there are also planarian species that reproduce sexually. And here’s an interesting factoid: you can sexualize an asexual planarian by feeding it a sexual one. Or cut out the cannibalistic middleman and just inject neoblasts from a sexual worm directly into an asexual one. They’ll move right in, take over, sexualize the territory.

So. Neoblasts are Immortal. Autonomous. Mobile. Genetically distinct. Neoblasts are, in other words, a system which maintains a higher level of internal cooperation and a lower level of internal conflict than either its components or the larger system of which it is a component (i.e., the worm entire).

There are quantifiers, of course. It wouldn’t be science if you couldn’t hang numbers off it. The paper cites Hamilton’s Rule, invokes “zygotic bottlenecks”, describes a model which simulates a day in the life of Joe Neoblast. But the conclusion, the point, is that planarians are not the organism here. Neoblasts—in their competing tribes— are the organisms, the individuals. The worm is merely the niche they happen to be fighting over. The worm is not an individual but an environment, highly complex, constructed by neoblasts out of their own “reproductively incompetent progeny”. Maybe it’s just me (I am also, after all, reproductively incompetent), but I find this a profoundly exciting thought.

And I haven’t even mentioned somatic mutations, bioelectrical fields that supersede genetic codes, two-headed and headless variants that persist from one generation to the next even though the genes themselves have not been edited. Fields and Levins invoke all that stuff. But for me, their radical conclusions regarding individuality are especially resonant in the context of John Carpenter’s classic “The Thing”. So much of planarian biology seems, paradoxically, both alien and familiar. The ability to grow new morphological features independent of genetic code. A single particle able to regenerate an entire organism (“We should each prepare our own food. And I suggest we only eat out of cans.”). Even the alien’s Achilles’ heel, the competing agendas of different groups of neoblasts (“Blood from one of you Things won’t obey when it’s attacked. It’ll try and survive—crawl away from a hot needle, say.”)

It all fits.

Canonically, The Thing came from outer space. But maybe that’s not where we should have been looking all this time.

Maybe we should have been looking at the puddles under our own feet.

- Admittedly the last two words are redundant, but I don’t want to lose sight of the idea that antagonist process do persist to some extent. ↑

More reasons to be charmed by those cross-eyed little planaria! Ever so glad I put a flatworm pattern into my Science Critters book that’ll be released this fall.

For years I’ve been throwing symbiosis and mitochondria at weirdo libertarians and randians whenever they bring up any of their ‘animal spirits of competition’ or the ‘creative destruction’ &tc. But I usually get pushed back to some squishy bs myself. Thanks for pointing out these papers, I’ll have some ammunition.

tl:dr, arguing back against “It’s nature” is haaaard when you don’t have a good counterdefinition.

Greggles,

Why treat “it’s nature” as if it’s a valid argument to do anything anyway? Nature does lots of horrible, horrible things.

I am reminded of Tasmanian Devil facial tumour disease.

The actual engineering of cooperation is sufficiently important that organisms have evolved to accept a remarkably high cost in order to assure it: universal organismic death. Limited, determinate maximum lifespans combined with arranging that the next generation arises from a single cell, assures that self-aggrandizing cells gain no purchase on future generations unless they are, or can alter, germ cells.

However, I remain fascinated and deeply puzzled by instances where highly complex and apparently fragile coordination is maintained without “zygotic bottlenecks,” i.e without accepting the cost of universal mortality. Why don’t competing planarian cell lines tear them to pieces? Two more examples of this puzzle: sponges are one of the oldest multicellular life patterns, and thy constitute a “voluntary” association of separately reproducing cells. you can pass a sponge through a net fine enough to separate it into individual cells, and those cells will rejoin into a new sponge. And yet, there seem to be obvious ways that sponge cells can free-ride on the colony. Each cell expends energy to help pump water through the sponge. Why don’t non-pumping sponge cells destabilize and take over sponge colonies? Also for a long time biologists have told that eusocial species like ants and bees maintained their cooperation in a similar way to eukaryotes, again, at a big and obvious cost in reproductive fitness, through narrowing genetic inheritance through a single queen and keeping the vast majority of hive/nest members sterile. It’s a clever and persuasive story, except it happens to be false. There are many species of eusocial insect that maintain multiple queens in every group. Nowak, Tarnita & Wilson, “The evolution of eusociality” https://www.nature.com/articles/nature09205 What stabilizes cooperative behavior in these species? As best I can tell, by behaving in accordance with the much-maligned theory of group selection.

Dawkins responded to these assertions with such virulence that the usually imperturbable Wilson referred to him publicly as a “science journalist.” Cold!

Wait a minute. What? If a sexually reproducing neoblast joins an asexually reproducing planerian, which gene lines end up in the germ cells?

I’d bet art long odds that it is the genes from the invading sexual neoblasts exclusively, or at least, highly disproportionately. It’s like those “slaver” ant species that make their living by invading the colonies of different species of ants, killing the queen, and then sending out the same chemical signals so the colony raises the invaders’ offspring as their own.

However, I think it would be much more interesting if I was wrong.

Hello Mr. Watts,

No shortage of interesting stuff in Mr. Fields’ website, it seems:

https://www.chrisfieldsresearch.com/

What is your opinion on his (hot?) take on consciousness:

https://iai.tv/articles/dont-worry-about-the-hard-problem-of-consciousness-auid-1373

(first comment, but long-time lurker and admirer!)

Fascinating. I wonder what the implications are of lichens? In relation to that, I recommend Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life (it’s about fungi).

Fucking Awesome, which I want to spell out in capitals, but I won’t, because… the internet doesn’t need people shouting.

Still, fucking A!

Yep. Just what I need to blow my mind wide open. And yes, I’m stealing the insight and going to running off into the darkness, laughing crazily with my new piece of a puzzle to add to my to my insane prognostication on life in the universe and as an answer to the Fermi question.

Thank you.

So does any of this lend support to the ideas of Rupert Sheldrake? Lots of talk about bioelectric and morphogenetic fields. Sounds familiar.

“These results suggest that planaria have not fully completed the transition to multicellularity, but instead represent

an intermediate form in which a small number of genetically-heterogeneous, reproductively-competent cells effectively

“farm” their reproductively-incompetent offspring.” <— it sounds cool but I'm not completely sold. I'd like to see a bit more evidence, for example regarding the genetic heterogeneity. They only refer to one paper talks about that, but they check the heterogeneity of a clonal population of planarians. What I'd really like to see is the intra-organism genetic heterogeneity in the neoblasts, although that's probably not easy, but can probably be done nowadays with single cell genome sequencing.

But yeah nature is full of weird organisms. We often take it for granted because so much research has been focused on a few model organisms (that each have their own idiosyncracies as well, to be fair, e.g. drosophila use transposons to extend their telomeres iirc) that we forget there's a whole bunch of other things out there.

Speaking of weird organisms, I'm sure we're all familiar with parasitic wasps here. You know, laying an egg inside another organisms and devouring it from within, the inspiration for Alien which is the best movie ever etc.

But did you know that some species of parasitic wasps have something called "polyembrony" where the embryo at an early state splits into multiple embryos and some of them become something called "precocious larvae". These precocious larvae develop quickly but never reach maturity and die inside the host, and it turns out their purpose is to kill the larvae of competing parasitic wasps.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jez.1402370303

I think you would enjoy learning more immunology PW. The utter collapse of immunoregulatory law and order in chronically inflamed settings like cancer, it’s like a movie. The system starts breaking down. Individual cells, unable to turn themselves off, simply potentate their own activity through helplessly antagonising neighbouring tissue, drawing in fresh recruits from the blood before hitting them with the same milieu that corrupted them. A successful immune response isn’t a symphony of cooperation, it’s simply a sum of the parts of the parts of the immune system cooperating outweighing those which have, in parallel, gone terribly wrong.

“Information, shaped by natural selection”

Sentient cat memes will eat the universe.

osmarks,

Who said I accepted the argument?

Problem is you can’t change a worldview in one conversation, you usually need to keep them sleep deprived, somewhat malnourished and isolated from their support network for at least a couple of weeks.

So sometimes you might need to accept someone’s framework of beliefs if you want to change their mind on one point.

Certainly the most “unique” post-election analysis I’ve come across so far.

I’m pretty sure I already posted links to Michael Levin‘s work on bioelectricity and regeneration, but perhaps they got lost in the churn, the man seems to have discovered the actual programming code of large scale biological structures and has come up with some fairly impressive demos (All sorts of Frankenstein stuff with planarians, but also those freaky xenobots made out of frog cells)

Not that I’m accusing any present company of this, but there’s not only a tendency for some people to defend a given behaviour by saying it’s “natural”; there’s also a tendency of some people to assume that whenever some defines something as “natural” they’re defending it as a good thing.

As I am (probably too) fond of saying, behaving “naturally” is what got us into this mess in the first place. If we want to get out of it we’d better start behaving unnaturally ASAP.

Thanks for this. I admit I was a bit unclear on the value of the whole bottleneck thing.

Is it still much-maligned? I know it was back when I was in grad school, but I had the sense that things had changed since then. For one thing, they rebranded it as “multilevel selection”. For another, apparently they established that the models which ruled it out had some pretty unrealistic and arbitrary constraints. And even back in the eighties, nobody denied that sacrificing your life for the tribe (for example) could enhance inclusive fitness by benefiting your relatives, even though that manifested at a group level. We just called it “kin selection” instead.

Yeah, I think that’s what the paper’s saying. Except apparently you’d get genes from sexual and asexual neoblasts mixing it up at wound sites, so the genotype of any given neoblast line would change over time, even within a single corpus.

And I thought my first website looked premillennial. Some of those slides do look fascinating, if only you could slow down the playback speed to something on the safe side of epilepsy-inducing…

I think he’s more or less right, with the caveat that— while, yes, the panpsychic claim that “consciousness is a fundamental property of all matter” doesn’t really explain anything—it’s no less explanatory than “mass is a fundamental property” or “charge is a fundamental property”. In all these cases we just accept the label and play with what those properties do and how they interact, so I don’t see why we should hold consciousness to a different standard if you grant the Fundamental Property premise.

But, yeah. None of the models he cites even hints at solving the hard problem. I’m currently finishing off a book that claims to solve it, but as enlightening as it is along other axes, the bottom line seems to be “these structures exist as a delivery platform for feelings, and you can’t have a feeling without feeling it, therefor consciousness”. Which is true in a trivial sense at least, but seems a bit too circular for my liking.

All that said, I disagree with the conclusion that we should just ignore the problem and focus on correlates. I think it’s a profound problem. I would really like to see someone make headway on it. I don’t have the first fucking clue how you’d go about doing that, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be done.

Maybe Searle’s right and we have to completely reinvent physics.

Jesus, you may be right. I don’t remember much about Sheldrake’s fields—I read a few pop-science pieces about it, back around the turn of the century— but now that you mention it, it does seem kind of similar.

I’ll defer to your expertise on how compelling the presented evidence is. Fortunately, as a skiffy writer I get to just take a cool idea and run with it. The fact that it appears in a peer-reviewed journal just gives me cover if it turns out to be wrong.

Whoa. That is so cool.

I wonder if I can use that somewhere…

That sounds almost like a metaphor for us…

You’ve lost me. Especially since I wrote this pre-election.

“Information, shaped by natural selection.” I’m not as familiar with planaria as most posters here, it seems, but I do remember studying them in school many years ago. I just thought they were worms ‘cuz that’s what our teacher said.

What a crazy organism if neoblasts are the actual organisms within its worm-like “landscape.” Maybe they’ll rise and populate Earth after we’re all stuck in virtual la-la land.

Maybe they already did.

Tangentially relevant: Scientists are now making unicellular yeast evolve multicellularity. Will They Never Learn?

https://www.quantamagazine.org/single-cells-evolve-large-multicellular-forms-in-just-two-years-20210922/

Not directly related to biology: there is a very interesting video I watched some time ago describing the concept of Combine from Half-Life series. In game itself there’s never, really, like, direct and extensive description of who they are and where they come from, only a lot of hints and references. And I am quite sure the creators don’t bother to develop this understanding further to keep their hands free for the future changes.

In any case, the major conflict of the series is the opposition of Human Resistance to the whole of invading Combine. For one, the city’s Overwatch refers to protagonist as “individual” (directly addressing or announcing), as opposed to the whole of the Combine itself. On the other hand, the same Overwatch refers towards other Combine assets within itself in medical terms – “lock, cauterize, stabilize”. It gives the very distinctive impression of them being a collective alien intelligence interacting with humans on its own terms. Along with completely Orwellian effect it gives to the entire concept, of course.

And yet they are not presented as hive-mind, but rather like a giant corporation. So, very much like Planarians, they are creatures of different lineages, who cooperate within the whole “body”, to achieve goals that do not belong too any of them individually (or to their origin species), but rather out of collective self-interest.

Hey Peter, on the subject of pithy definitions, you ever read this one from Cormac McCarthy? “The unconscious is a machine for operating an animal.” It’s from this essay he wrote in 2017: https://nautil.us/issue/47/consciousness/the-kekul-problem

Seemed up your alley, but I could be wrong. Would be interested to get your take on the quote, the essay, and even McCarthy’s fiction if you’re up for it! Thanks for considering.

I personally loathe arguments based on ‘nature’ but I’ve found when arguing against a position based on a (highly arbitrary and narrow interpretation) of ‘nature’ it’s better to come up with counter examples rather than attack the overall structure of beliefs.

So, while Dawkins talks about the “selfish gene”, we should really talk about the “selfish neoblasts” when the topic is organisms like flatworms.

Seeing life as information sounds like biosemiotics, as proposed by the late Jesper Hoffmeyer.

“The major evolutionary transitions, including those from prokaryotes to eukaryotes and from free-living cells to multicellularity, all increase the scale over which cooperative interactions dominate competitive interactions.”

According to Stephen Wolfram’s A New Kind of Science, there is a universal upper limit for complexity in any system. If true, there should be a limit for how complex a prokaryotic cell can be (some can grow very big, but not more complex, and is usually less efficient). An eukaryotic cell is a system made up of units that are themselves systems, such as organells like mitochondria and chloroplasts, and new structures. When these cells has reached the upper limit of their complexity, a new system can be created by going multicellular. And social behavior in for instance ants becomes more complex the more members the colony have and the more specialized the casts are, till a certain point. They reach a stage where the colony may continue to grow, but without achieving more complexity.

The same with human cities. I don’t remember the number, but the more humans that live in a city, the more ideas, inventions and progress we will see, till we reach a certain number (one or two million or so), and nothing more can be gained for a bigger population.

“It told me that carbon and silicon were just platforms, that a piece of software could be not just metaphorically but literally alive under the right circumstances.”

Yes, the “hardware” alone will always be non-sentient. Most have heard about the conscious, the subconscious and the unconscious in psychology (and according to Jung also the collective unconscious). But we could just as well call it the non-sentient, the sentient and the consciousness.

You have pointed out before that the brain can only contain a single consciousness at the time. And yet that single consciousness can hear voices and see hallucinations of a kind that one associates with a conscious mind. An inner voice having a long monologue with you is not just random signals, it is just as complex as a monologue from a real human.

So, just as leaf-cutter ants and a fungus have co-evolved, these mental phenomena indicates that our mind is made up of both conscious, sentient and non-sentient processes, all of which have co-evolved to fulfill each other. If you hear voices, this balanced cooperation between the processes no longer function properly.

Like when you try to remember a name or the title of a song. You can’t remember it, and you continue to talk about something else, and suddenly the name just pops up into your mind all by itself. Which is probably the result of the non-sentient processes in your brain. Or when you hear the narrator on the radio say something, but don’t understand what it was he said. A minute or so may pass, and suddenly you realize what he said.

These processes should be hard working when a child is developing for instance a language.

This is getting a bit off topic, but regarding consciousness; it is said that the human body sends 11 million bits per second to the brain for processing, yet the conscious mind seems to be able to process only 120 bits per second or so. Another upper limit of the complexity Stephen Wolfram is talking about?

But are emotions included in these 120 bits per second? If for instance a teenage girl have recently developed an obsession with The Beatles, and she is watching a TV-recording of one of their songs which she so far has only heard on CD, her heart may be filled with emotions and she is practically in nirvana. It’s the music she loves, maybe she is also deeply in love with the younger version of Paul or John, it’s the nostalgia and atmosphere and all. Her father is sitting in the couch and is watching the same thing. He is a pod person; he hears the music but it doesn’t trigger any strong emotions in him. He cares zero about the members of the band or anything. Emotionally, he is completely flat.

A telepath that is also an empath, feeding on emotions, would gorge on the daughter’s emotions but only get a small bite out of the father.

The question is; does both the father and the daughter experience the world in 120 conscious bits per second? If they are, and it is all information processing, then emotions must be something more than that.

This competition/cooperation ratio seems to be the key concept, I wonder if anyone measured it across different systems. It seems almost as a subtype of the noise/signal ratio.

Greggles,

“Animal Spirits” is a Keynesian concept, libertarians tend to be more interested in Austrian economists.

Greggles,

There aren’t just examples that go against “Darwinian” evolution, competition doesn’t even make sense. For most of the history of life there has been enough resources for all species to get along just fine, the reason being that individuals are constantly selected for in a resource-limited environment for billions of years. Species co-evolve to co-exist, and this coexistence is with the rest of nature/the environment is what makes life on earth successful and resilient.

I’ve also spoken up for SPEAK, from the perspective of a conservative evangelical Christian who did choose to be selective about her own reading in high school and respects teens and parents who want to do likewise — but doesn’t think SPEAK should be pulled from schools: http://rj-anderson.livejournal.com/630566.html

Chase,

Thanks for pointing that out. Would you mind telling what reductive phrase the libertarians prefer? I’d appreciate it.

Actually, I thought learning was kind of the whole point…

I went back and forth with Marc Laidlaw on this very issue, back in the day. I’m pretty sure even they didn’t really know what the Combine was.

Honestly, I’m not sure. I know I read an essay by McCarthy on consciousness and language, but this particular one looks unfamiliar at first glance.

As for the man’s fiction, the only piece I’ve read was Blood Meridian. It was incredible. There were places I had to stop and read the prose aloud to myself, just to marvel at it.

Still haven’t read The road, surprisingly. Got a copy lying around somewhere.

I think the quote I invoke is something to the effect that a single substrate can only host a single consciousness. But you can split that substrate into two, and hello Split-Brain personalities…

I can’t speak to Wolfram’s upper limits (I just floundered through his massive post on parallel-timeline-consciousness and it just about killed me), but I’ve read that minuscule bps myself. It blows my mind (which is easy, given that that would apparently only take 129 bps). I find it viscerally inconceivable that even the image of the small part of the keyboard I’m currently perceiving, with its colors and letters and topography— not even including the tactile and auditory feedback I perceive as I type— could possibly be crammed into 128 bits per second. Add in random thoughts, the feel of a cat at my side, the BUG grumbling next to me on the couch…it seems impossible.

I don’t know where that number comes from, I’m no expert, I can’t contest it. But it can’t be that simple. There must be some caveat or variable I’m not considering.

Yeah. You could come up with a hard Individuality Index. Use it to arrange seating at restaurants and suchlike…

Um, you do realize that sentence contradicts itself, yes?

128 bps is plenty with many processes occuring asynchronously at short distances. Synchronous concepts of data rates and linear processing can’t really apply when talking about highly-networked neural systems… Analog logic and whatever crazy architecture millions of years of evolution come up with is just not something we can even think about matching efficiency with our current technology.

There’s a whole book about this – “Surfing Uncertainty” by Andy Clark. Seems like a very important book, you should read it if you haven’t.

“Information, shaped by natural selection”

I recommend we cut the Straw Darwinists loose by adopting the following version instead:

“Information, filtered through survivorship effects”

Oh, and also. If you’ve got your head around the idea that life is information, and your mind is blown by the idea of organisms being just titanic biomechanical generation ships for the benefit of certain of their cell lines? Now incorporate this thought germ:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rE3j_RHkqJc

(Spoiler:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

… we’ve been a substrate at least since we developed fictive recursive language. Moreover, we’re not the “organism” which calls the shots on this planet.)

Me again! Holding up the afterlife of this thread with one more “one more thing”.

That definition of “individual” that you quoted sounds eerily reminiscent of these.

https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a34272219/weird-circles-nature-alan-turing-patterns/

Chase,

Chase Ebert?

Donald Hoffman mentions this in his last book “A case against Reality”. (Par 15.6 ff):

“Our senses forage for fitness, not truth. They dispatch news about fitness payoffs: how to find them, get them, and keep them.

Despite their focus on fitness, our senses confront a tsunami of information. The eye sports 130 million photoreceptors, which collect billions of bits each second.1 Fortunately, most of those bits are redundant: the number of photons caught by a receptor differs little, in general, from the number caught by its neighbors. The circuitry of the eye can, with little loss in quality, compress those billions of bits down to millions—just as you may, with little loss in quality, compress a photo. It then streams the millions of bits to the brain through the optic nerve. This stream, though compressed a thousandfold, is no gentle brook. It is a flood, which would overwhelm the visual system if untamed. Taming this flood is the job of visual attention. Billions of bits enter the eye each second, but only forty win the competition for attention.2

The initial descent from billions of bits to millions loses almost no information—like a book manuscript edited to omit needless words. But the final plunge to forty loses nearly everything, reducing the book to a blurb. This blurb must be tight and compelling—just the essentials to forage for fitness. This may feel at odds with your own experience of a visual world that seems packed, from corner to corner, with myriad details about colors, textures, and shapes. Surely, it would seem, we see more than just a headline, we see articles, editorials, classifieds—the whole works.”

He goes on with some examples about change blindness and evolutionary fitness but it comes down to the idea that our visual perception is quite an illusion. Only very small, fitness relevant parts get updated with small amounts of information. Seems to be similar for our other senses. So there are some massive cogntive spam filters in place the reduce the floods of information comming from our photorecetors and other nerve cells down to an optimised fitness relevant trickle that can handled by our brain with acceptable reaction times.

His approach to the hard problem of consciousness is quite radical. He builds upon evolutionary processes – survival of the fittest and it goes as far that he questions Reality itself. In his Interface Theory of Perception he argues that even space and time are just illusions of our evolution in search of fitness payoffs and that the true nature of reality is not only unknowable but could be radically different from what we belive it is. If I get it right, what is not easy because it is sooo radical, he declares consciousness as fundamental and materiality, space, time etc… an derived illusion of conscious agents which are always changing in search of fitness payoffs in a reality which could be radically different from what we think it looks like.

Its quite a good read and I get some strong Philosophie (Kant’s “Ding an sich”) and Holographic universe (Physics) vibes from reading it, just this time from an evolutionary biology viewpoint.

Reading stuff like this always gets me thinking about holons and if something like a corporation or a conglomerate could, in a sense, be considered a living thing. I mean it’s subject to “natural” selection it does maintain a higher level of internal cooperation and all that.