It Awaits Your Experiments.

You may have heard of Christian Bök. You may have read about him on this very blog if you’ve been hanging out here long enough. Perhaps you were even one of the very select few to witness the seminal talk I gave back in 2016[1]—“ScArt: or, How to Tell When You’ve Finished Fucking”— which climaxed with a glowing description of Bök’s magnum opus, then still in progress. And if you read Echopraxia, you’ll have encountered—without even knowing it— a brief cameo of that work near the end, suggesting that at least in the Blindopraxia timeline, he’d brought his baby to fruition.

Truth to tell, I didn’t know if he was actually going to pull it off for the longest time. I thought he’d given up years ago.

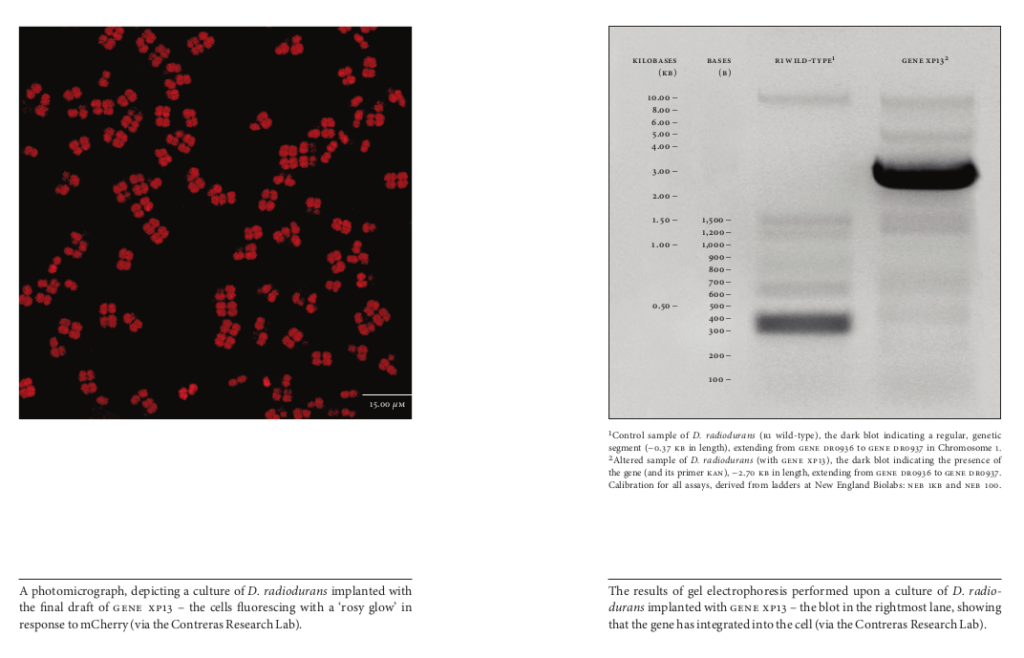

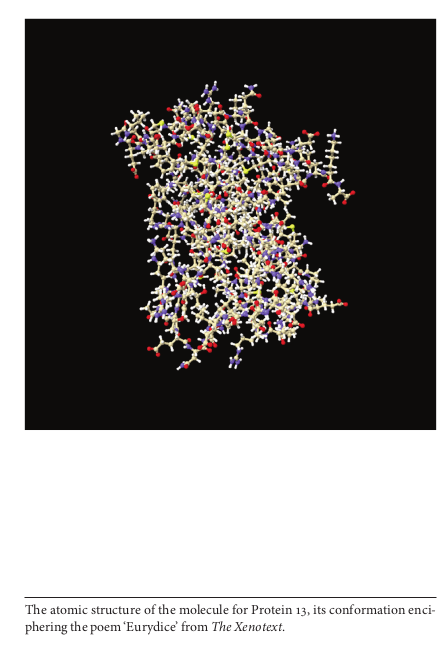

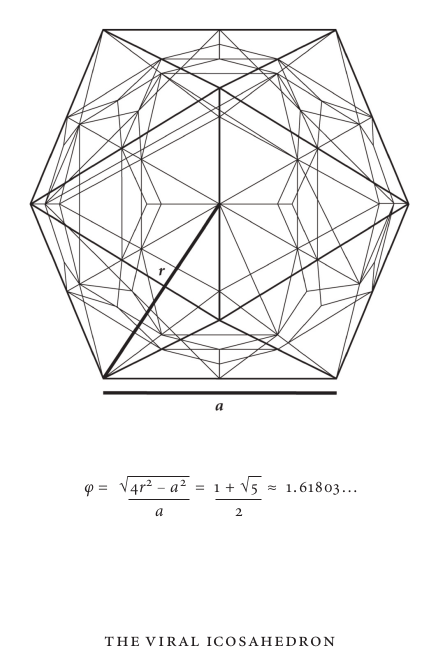

The story so far: back in the early two-thousands Christian Bök, famous for accomplishments lesser poets would never even dream of attempting (he once wrote a book in which each chapter contained only a single vowel) started work on the world’s first biologically-self-replicating poem: the Xenotext Experiment, which aspired to encode a poem into the genetic code of a bacterium. Not just a poem, either: a dialog. The DNA encoding one half of that exchange (“Orpheus” by name) was designed to function both as text and as a functional gene. The protein it coded for functioned as the other half (“Eurydice”), a sort of call-and-response between the gene and its product. The protein was also designed to fluoresce red, which might seem a tad gratuitous until you realize that “Eurydice”’s half of the dialog contains the phrase “the faery is rosy/of glow”.

Phase One involved engineering Orpheus and Eurydice into the benign and ubiquitous E. coli, just to work out the bugs. Ultimately, though, the target microbe was Deinococcus radiodurans: also known as “Conan the Bacterium” on account of being one of the toughest microbial motherfuckers on the planet. To quote Bök himself:

Astronauts fear it. Biologists fear it. It is not human. It lives in isolation. It grows in complete darkness. It derives no energy from the Sun. It feeds on asbestos. It feeds on concrete. It inhabits a gold seam on level 104 of the Mponeng Mine in Johannesburg. It lives in alkaline lakelets full of arsenic. It grows in lagoons of boiling asphalt. It thrives in a deadly miasma of hydrogen sulphide. It breathes iron. It breathes rust. It needs no oxygen to live. It can survive for a decade without water. It can withstand temperatures of 323 k, hot enough to melt rubidium. It can sleep for 100 millennia inside a crystal of salt, buried in Death Valley. It does not die in the hellish infernos at the Städtbibliothek during the firebombing of Dresden. It does not burn when exposed to ultraviolet rays. It does not reproduce via the use of dna. It breeds, unseen, inside canisters of hairspray. It feeds on polyethylene. It feeds on hydrocarbons. It inhabits caustic geysers of steam near the Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park.

I’d love to quote all seven glorious and terrifying pages, but to keep within the bounds of Fair Use I’ll skip ahead to the end:

It is totally inhuman. It does not love you. It does not need you. It does not even know that you exist. It is invincible. It is unkillable. It has lived through five mass extinctions. It is the only known organism to have ever lived on the Moon. It awaits your experiments.

As things turned out, it had to await somewhat longer than expected. The project hinged upon molecular techniques that did not exist when the experiment began. Christian taught himself the relevant skills— genetics, proteomics, coding— and enlisted a team of scientists (not to mention a supercomputer or two) to invent them. His audacity was more than merely inspiring; some might even call it infuriating. As I railed back in 2016:

It was fine when Art came to science in search of inspiration; that’s as it should be. I suppose it was okay— if a little iffy— when Science started going back to Art for solutions to scientific and technical problems. But this crosses a line: with The Xenotext, we have reached the point where Science is being used solely to assist in the creation of new art. Scientists are developing new techniques just to help Christian finish his bloody poem.

Up to now, we’ve generally been in the driver’s seat. Insofar as a relationship even existed, Science was the top, Art the Bottom. But Art has now started driving Science. Science has discovered its inner sub.

As a former scientist myself, I was not quite sure how to feel about that. But however that was, I knew Christian Bök was to blame.

Fortunately, Science got a reprieve. The project hit a bump at E. coli. Eurydice fluoresced but the accompanying words got mangled. When they eventually cleared that hurdle and moved to Phase Two, Deinococcus fought back, shredding the code before it ever had a chance to express. Conan, apparently, does not like people trying to play with its insides. It’s already got its genes set up just the way it likes them. Unkillable.

That, as far as I knew, was where the story ended ten years ago. Christian released The Xenotext: Book One in 2015, documenting his efforts and gift-wrapping them in some gorgeous and evocative bonus content, but the prize remained out of reach. He headed off to Australia to follow other pursuits; then to that oversurveilled and repressive shithole known as the United Kingdom. We fell out of touch. I assumed he’d given up on the whole project.

Oh me of little faith.

Because now it’s 2025, and he fucking did it. The Xenotext is live and glowing in Deinococcus radiodurans: iterating away inside that immortal microbial bad-ass that feeds on stainless steel, that resides inside the core of reactor no. 4 at Chernobyl, that does not die in the explosion that disintegrates the Space Shuttle Columbia during orbital reentry. Christian Bök did not give up. Christian Bök did not fail. Christian Bök is going to outlive civilization, outlive most of the biosphere itself.

The rest of us might think we achieve artistic immortality if our work lasts a century or three. Bök blows his nose at such puny ambitions. His work might get deciphered by Fermi aliens who finally make it to our neighborhood a billion years from now. It could be iterating right up until the sun swallows this planet whole.

It’ll almost certainly be around for Dan Brüks to find in the Oregon desert, mere decades down the road.

The Xenotext: Book Two comes out from Coach House in June 2025. It would be well worth the price just for the the acrobatics and anagrams and sonnets, for the way it remixes science and fiction and the classic canon of dead white Europeans[2]. It contains poetry to entrance people who hate poetry. It juggles space exploration and the Fermi Paradox and the potentially extraterrestrial origins of Bacteriophage φx174. But its rosy flickering heart is that dialog iterating away in Conan even as I type. A reinvention, almost a quarter-century in the making. A fucking monument if you ask me, equal parts revelation and revolution.

If you happen to live in or around Toronto, it’s getting an official launch on May 27 at The Society Clubhouse, 967 College St, from 7-9pm. It’s one of a half-dozen Coach House titles that will be launched that night, and no doubt all six authors are worthy in their own right. Still. You know who I’m going for.

Maybe I’ll see some of you there.

Literature encoded into juggernaut microbial genes by a man who, facetiously taking at face value the Mooring-dialect North Frisian meaning of his surname, is literally called Bible.

Clever. But can it sing “Row, row, row your boat”?

I think that’s on the list. Right after “evolve opposable thumbs”.

A bacterium with opposable thumbs? Fair shot, it can’t do much worse than H sapiens has.

Several lifetimes ago, waaaay back when I was hilariously crashing out of premed, I can remember the biochem prof cited this one weird trick—where a single DNA sequence expresses multiple proteins just by adjusting the read offset—as evidence of God’s handiwork. Although personally I think it much more compelling evidence that Earth is a vast massively parallel supercomputer with lovely crinkly bits grinding the combinations for

10 million3.5Bn years.Never send a brain to do an algorithm’s work, that’s my motto nowadays. And DNA’s already halfway to Forth.

Tip o’ the hat to Mr Bök for his God-level advance trolling of whatever race of hyperintelligent cockroaches eventually arises in our wake.

Only the paperback?

What is wrong with the publishing industry today? If I’m okay with read-and-forget, I’d buy a pdf or whatever the current thing is, epub or mobi or whatever. If I’m willing to both shell out and spend the precious shelf space in my shoebox of a domicile on some sliced dead wood, I’d want it to be durable. Physical. Bequeathable. Hard-cover.

What’s this obsession with paperbacks? They don’t really last, and don’t save any more trees either.

And I’ll be fucked if this right here is the kind of literature one reads on the tube during the commute, folding the corner instead of a bookmark before shoving it into the pocket of one’s coat.

Xenotext doesn’t need to be read by puny meatsacks. Xenotext is immortal.

I mean, the text that is not meant to be read, the signal that is not meant to be received, the meaning that is not meant to be understood is just noise. Isn’t it? And a large part of our problem right now is we make too much noise. Not in the sense of loud sounds, but in the sense of rubbish, garbage, bonkers signals. Rorschach is known to consider these things an attack.

I’m not the only person who finds paperbacks easier to read.

Oh really? I this a thing? I wasn’t aware it was. I have acquaintances who claim superiority of paper over digital, but I’ve never heard of hardcover vs paperback before.

Depends. A hardcover with a proper binding so the book stays open on its own is definitely easier to read and way more pleasant to the touch. Those are not even the norm in germany, mekka of well bound books, anymore, though. Our teacher at the booksellers school called those “book sex”.

These days i´ll settle for a paperback with proper paper where the ink doesnt smudge after softly touching it.

>Christian taught himself the relevant skills – genetics, proteomics, coding –

Sentences like these demonstrate the enormity of some peoples sheer intellectual superiority. Compared to a dude like him, i might as well be pond slime, happily gurgling away mindlessly in some nutrient broth. I am beyond impressed.

Holy shit, this is one of those stories that remind you to never quit art, even if you are not sure if you are on board with this life thing anymore. Thank you for bringing it up, Dr. Watts 🙂

Nice.

Apropos of nothing, apparently quantum energy teleportation has been confirmed. It’s not the telematter stream sending antimatter yet, but it looks interesting.

One can hope we will NOT live to see ads casually added into someone’s genetic material …?

Well, by the time Echopraxia takes place, you can apparently find the specs for the Denver sewer system in genes, so…

If it encodes a useless protein, does that make it a disadvantageous trait that will be eliminated by selection pressure?

More likely it’ll be selectively neutral; a single gene doesn’t take a whole lot of energy to maintain, and our own genomes are loaded with useless-but-non-deleterious code that’s accumulated over our evolutionary history. If there were some teensy Deinococcus-eating predator out there that hunted by sight, I suppose the glowing Conans would be more vulnerable to predation. Otherwise I don’t think it would make much difference.

Ah. What I think is more like this: synthesising bioluminescent proteins consumes organic matter but produces no benefit. This should at least cause natural selection to favour their unmodified counterparts?

Perhaps we should also deploy some versions with gene poem that don’t express, just as a backup.

“Useless” is relative: to random mutation it’s all raw materiel. Sure it’s non-coding today, but rotate a few bits just-so and it’s sharks with fricking laser beams evolved on their heads tomorrow.

[…] Read More […]

ewww.

You just copypasted a few paragraphs from this article under another name on a random website to get a backlink?

what a shame

I did not. Someone scraped this post without attribution.

ewww.

Did you just copy paste a few paragraphs from this article under another name on a random website to get a backlink?

what a shame

It’s spammy bot BS. Pay it no heed.

: : : DO NOT TAUNT THE XENOTEXT : : :

Nature of humanity, bud. We will poke it with a stick.

You’ve heard about Moore’s law but have you heard about Carlson curve? It’s a similar thing but for DNA sequencing. Between the year Bök has begun his work and the current year the cost of DNA sequencing has been reduced by 200%. In twenty something years any basement dwelling punk might pull this off.

I hadn’t, so looked it up. WP’s graph is lagging but it looks like cost has dropped a whole magnitude over the last 10 years. Did you mean 2000%?

Quite impressive when the 2001 bill for a human genome was $100M and now it’s approaching $100. Six magnitudes. Moore, clocking 4, looks distinctly sedate. I like my cyberpunk with 1980s electronics and 2080s genomics.

“I just do eyes…” Damn straight.

—

Apropos of other things, tweaking Interstellar’s “Mountains” to ⅛ tempo makes an interesting Oort cloud experience for those needing a Big Ben fix. (Use a YouTube downloader to grab it as .mp3 file as YT shits ads all through it otherwise.)

They use it to track dog poop infractions so it must be cheap nowadays

What kind of maths is this? 200% reduction implies that it was reduced to zero, and then reduced by its cost again, so whoever wants to sequence something should be paid for it. So if the cost was 1000 bucks, now after a 200% reduction you’d receive 1000 bucks if you order a sequencing.

200% = 2.0, so a reduction would be one-half of the original cost. I suspect that wasn’t what parent intended. Never trust percentages, shifty sods.

One half of the original cost is 50% reduction or one half reduction. You could say it’s “twice as cheap as it used to be”. Reduction “by 200%” is reduction by twice the current value, i.e. v – 2*v = -v. Percentages are not shifty sods, it’s someone’s school maths that’s shifty.

If someone says “this thing is 75% cheaper” that would mean it’s one quarter of its original price. But somehow, in your world, saying “this thing is 200% cheaper” is just one half of its original price? I mean, with this kind of maths you’d struggle with Mendel’s law, forget DNA sequencing.

I looked it up and you are right, I stand corrected.

Funny story re. school math: I was top student in my big exam year, then failed it in 6th year studies. Dropping from 98.5% to an E grade may have been a record.

Although even back then I could never get date math right, prone to off-by-one errors. Like Peter’s scramblers, I could math without thinking; it was applying consciousness that bolloxed it up.

All of which is academic since university slagged the wetware completely. I couldn’t shape-rotate a circle now: there’s just gray static where matrices and differential calculus once resided. OTOH, my language skills have improved, which is why I would have used the phrasing “reduced tenfold,” bypassing pesky percentages entirely. 🙂

Damn, that’s impressive. Not just that he pulled this off, but that he took his dedication to his art up to a whole different level.

Incredibly inspiring and impressive. But, to play the cynic, I worry the specific sequence (if not the entire protein itself) will be altered or lost entirely after several (if not a few) generations unless a selective pressure maintains the precise sequence. The hypothetical super-Bök molbio artist would have to generate a poem sequence which gives rise a protein of such unalterable importance to bacterial function that genetic drift is strongly selected against. Perhaps a bacterium is too simple an organism for this, and more complex life needs support this endeavour…

Goddammit, I think you may be right. My gut reaction was to assume that D. radiodurans is highly resistant to mutation because it laughs at radiation that would kill a tardigrade. Wikipedia even says that “Deinococcus should have little or even no mutation accumulation”, although it provides no citation. But then these guys over here say that it has a mutation rate similar to E. coli (although the “mutation spectrum” is different, whatever that is).

So, shit. Maybe the Xenotext won’t last a billion years after all. Although given that D.r. keeps so many copies of its genes on hand, and given that it apparently kicks ass at DNA repair, I can’t see why it still wouldn’t be pretty long-lived even if the gene is selectively neutral. Or maybe Bök et al have figured out how to buttress it somehow. I’ll have to ask him.

Methinks consumer available DNA data storage is gonna be a more overlooked problem. When that stuff breaks loose it’s gonna be difficult to tell apart the poetry from all the other unassuming data.

Just wait till your pretty poems evolve into Naked Lutefisk by Squid Burroughs.

Shoulda read the [very] small print. Ya gets exactly what ya paid for.

As chance would have it (actually, it was pretty much inevitable), Burroughs features prominently is a decent-sized chunk of The Xenotext Book 2.

Cut-up method worked for Brion Gysin. Who knows what Bök’s bugs might improv!

I mean, the next logical disruptive step in poetry should be innovative delivery to the reader.

Embed the Omniscience into something else’s DNA. Make people contemplate their life. Not anything gruesome, like internal bleeding. Diarrhoea seems reasonable. E. coli? Cholera would be a solid choice as well.

Let Bök one up that. “My Omniscience makes people literally shit themselves even before they read it” is the ultimate bragging rights.

Do it. You are a biologist. I know you insist on being a writer, but I bet being a biologist is just like riding a bike.

[…] Bök’s “The Xenotext Experiment” is a groundbreaking project that aimed to encode a poem into the DNA of a bacterium. […]

Reminds me of Stanislaw Lem’s spec-fic ‘Eruntics’ (or How to Teach Your Bacteria to Communicate in English). I wonder if Bök took inspiration from that.

Peter, you say you are a former scientist. Do you have any scientific publications?

Check out my c.v. under the headings “Scientific Publications” (Primary & Technical Reports). Chase it down with “Scientific Presentations/Invited Talks” if you’re so inclined. The same document also lists a handful of awards I got for my work back in grad school.

Seriously, though, you should just be able to use Google Scholar to find that shit. Or even just look at the Author page on this very website. Although granted, that would show a level of research initiative extending beyond the rote parroting of Putin pablum.

I look forward to checking my spam folder to see how you manage to argue that the Journal of Mammalogy and the Journal of Theoretical Biology are just puppet rags sponsored by time-traveling Ukrainians.

Damn, that was a downright nuclear flash-burn. (Rightfully so)

… though that would be awesome if it were true. (Though if it’s true, I’m not really sure why Ukraine has been repeatedly shat on by its eastern neighbour throughout history. You’d think they’d be able to win before they started.)

I had a great time, thanks for sharing the event, and it was nice to meet you!! ✨

Likewise!

dr No

Hi Peter

Given how meticulous you are with footnotes and citations, I have to ask—I’ve combed through The Xenotext and I can’t find the Deinococcus radiodurans bit you “quoted”, nor those seven glorious pages you mention as if they were the Necronomicon itself… (protected under the fair use violation spell)

Any chance you could give me the actual source for those lines—and, if they exist, the rest of those mythical seven pages?

I don’t know what to tell you: I’m looking at them right now, pages 12-18. Maybe you’re looking at The Xenotext: Book 1? There are two volumes: the “Extremophile” poem is in Book 2, which has only just been released.

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal – Good or Bad

Not related to this post but reminded me of the host.

It reminded The BUG of me too.

Also SMBC is my all time favorite comic.

Just the one webcomic then? Here’s a whole website, grasshopper: Bad Space Comics

Peter Watts has no need of lowly bacteria.

Peter Watts is already contagious.

Wow, there are some really interesting creative people on this planet.

Hi Peter!

Thank you for such interesting post.

Do you have plans for any other new stories this year, or will it just be the original of The 21-Second God? And full Hitchhiker of course

Regarding your latest Signpost entry on carbon emissions from Gaza there is a discipline called Conflict Ecology I thought you might find interesting for research purposes. You are probably more up on this than I am—

https://www.conflict-ecology.org/

And since there has been a lot of discussion on human population, here are a few links on how population datasets systematically underrepresent rural populations.

https://www.sciencealert.com/earth-could-have-billions-more-people-than-we-ever-realized

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-56906-7

Conflict Ecology. What a cool, yet inevitable field of study.

Now I have to write a story about that.

Bruce Sterling already did – competitive terraforming of a Martian crater. Can’t remember the name, unfortunately. Part of his Mechanist/Shaper series, i think.

> Now I have to write a story about that.

Looking forward to it!

Prolly best to write quickly. Ecology gets a bit academic once world goes Full Strangelove. Never go Full Strangelove.

(Related: I’ve just caught up.)

Unrelated to this post—was the gremlin in Outtake by any chance a wink to Rod Sterling’s “Nightmare at 20,000 feet?”

Nah. Gremlins is established in Freeze-Frame Revolution as just the word the ‘spores use to talk about the things that come out of the gates after them sometimes.

That was one of the better episodes, though.

A classic.

But what, no love for the remake?

You mean the movie or the Jordan Peele reboot?

Oh, right. Follow the link. Forgot about that one.

Better than either of them.

You just watch yourself. I’m a punny man. I have the deaf sentence on twelve systems.

Hear, hear!

Part of me wishes I’d put “deaf sentience,” further punning on a certain book known to this audience, but it’s probably best dialed back. There’s only so much pain a human can take.

I was going to make a very ham-fisted joke about the iluminati inventing pigeons to eat the leftover bread past our pain threshold, but the delivery was not unlike that of a gluten-intolerant past their own :p

Pain-au-chocolat, though… no limits there, gimme!

Was there a Q&A afterwards? Did you get to talk to the guy?

We’re actually friends. He’s based in England these days, but we hang out whenever he’s in town.

Were his parents fundamentalists?

I do not know. Why do you ask?

I could always ask him.

Because he was born Christian Book. I once knew a Phil Stone. I asked him if Phil was short for Philip and he said no. His parents had christened him Philosopher Stone. I thought he was pulling my leg but turns out the name was legit. He let me touch his head but alas no divine illumination. I guess his parents were hippies and thought the name was cool.

Meh. Isn’t this kind of ridiculously old hat at this point, like people thinking the Sex Pistols are cutting edge in 2025? I mean, given that in 2014 George Church already published his book REGENESIS in paper, electronic, and DNA versions —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Church_(geneticist)

— That Rob Carlson and others have been trying to get the DNA Information Storage industry off the ground for the last 15 years —

https://www.synthesis.cc/synthesis/2022/10/dna-synthesis-cost-data

— And that for heaven’s sake back in 2014 even mainstream novelist Richard Powers wrote a whole novel, ORFEO, about a guy who did exactly what this guy boasts about doing, though granted it may be based on Bok —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orfeo_(novel)

To be candid, even I know people who’ve done this (without being the bioweapons/biodefense industry) but haven’t been stupid enough to publicly boast about it.

I think you might have missed a couple of important details in your skim. To borrow your analogy, even when the Sex Pistols were “cutting edge”, nobody claimed their edginess was because they used drums and electric guitars.

No one’s saying that Team Bök invented the idea of DNA as a storage medium for non-genetic data (although they did need to invent entirely new techniques to implement that concept in this particular context). Hell, Star Trek: Next Gen played around with those concepts decades before the sources you linked to. Using DNA to store arbitrary data strings is trivial. What’s less trivial is storing a data string which both contains literary information and acts as a functional gene to code for a protein which not only contains additional literary information comprising a coherent literary response to the genetic component, but which also fluoresces in reflection of the semantic content of the poem itself. That’s a few stacked levels of accomplishment beyond hey, we can store the blueprints for the Denver sewer system in E. coli or Give us money and maybe we can get dark matter to sever labelled DNA strands. Not to mention that those other cool applications are still largely theoretical (as far as I know); The Xenotext exists.

Also curious as to why you’d think it “stupid” to publicize a work of art using techniques which are either old hat, or limited to the creative expression of classical Greek idioms. Are you afraid someone’s might corrupt Xenococcus to fluoresce at a frequency that induces epileptic seizures or something?

Now that would be a cool story. Maybe I’ll write it.

No. I would be afraid of visits from and discussions with people who could put me away in places I really don’t want to be. I pick my fights.

I don’t think you can induce epilepsy across any but a small percentage of the population that way. Your gut mcrobiome – in one of your stories — was much morepractical and interesting. Had any interesting thoughts about targeting specificity recently?

Just leave it with me for a bit…

Unrelated, but no doubt relevant to Crawl interests:

https://arstechnica.com/science/2025/06/a-shark-scientist-reflects-on-jaws-at-50/

A shark scientist? Isn’t that how you get friggin’ sharks with friggin’ laser beams on their friggin’ heads?

Gosh, I hadn’t thought of that. What a lucky coincidence that I’m stood first in the queue!

Try asking that AI what the world would look like if Jesus had died an infant (hooray!) and the pernicious dogma of Imago Dei had never been spread.

What the fuck.

Like, seriously, what the actual honest to god fuck.

This is way too early in the week for this kind of schizo sigma shit.

Thanks, preordered. I loved his Pronoia and Crystallography.

If in-depth involvement with science helps you find time for poetry, see my website.