SOMA

“If there’s an afterlife, is my place taken? Is heaven full of people who would call me an imposter?”

— Simon Jarrett, upon realizing that he is a digitized copy.

Ever since the turn of the century I’ve had a— well, not a love/hate relationship with video games so much as a love/indifference one. I’ve worked on several game projects that never made it to market, wrote a tie-in novel for a game that did. Occasionally my work has inspired games I’ve had nothing to do with; the creators of Bioshock 2 and Torment: Tides of Numanera cite me as an influence, for example. There’s a vampire in The Witcher 3 named Sarasti. Eclipse Phase, the paper-based open-source role-playing game, names me in their references. And so on.

For one reason or another, I’ve never got around to actually playing any of these games. But a fan recently gifted me with a download of Frictional Games’ SOMA, whose creators also cite me as inspirational (alongside Greg Egan, China Miéville, and Philip K. Dick). And in the course of the occasional egosurf I’ve stumbled across various blogs and forums in which people have commented on the peculiar Wattsiness of this particular title. So what the hell, I figured; I needed something to write about this week, and it was either gonna be SOMA or my first acid trip.

Major Spoilers after the graphic, so stop reading if you’re still saving yourself for your own run at the game. (Although if you’re still doing that a solid year after its release, you’re even further behind the curve than I am.)

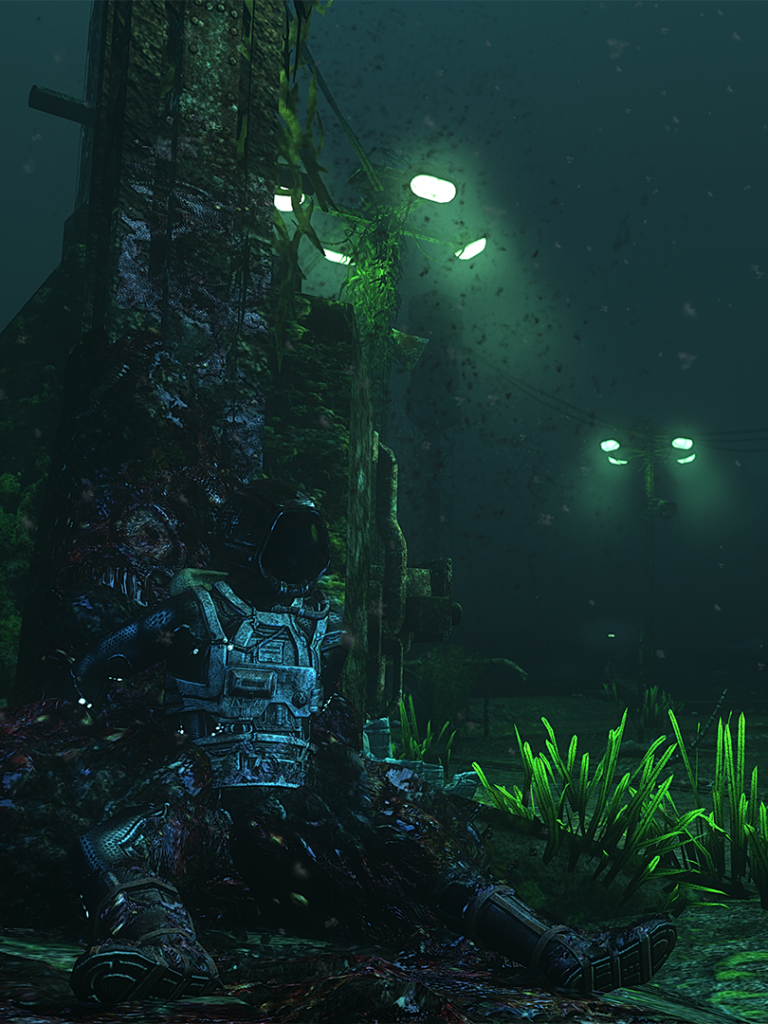

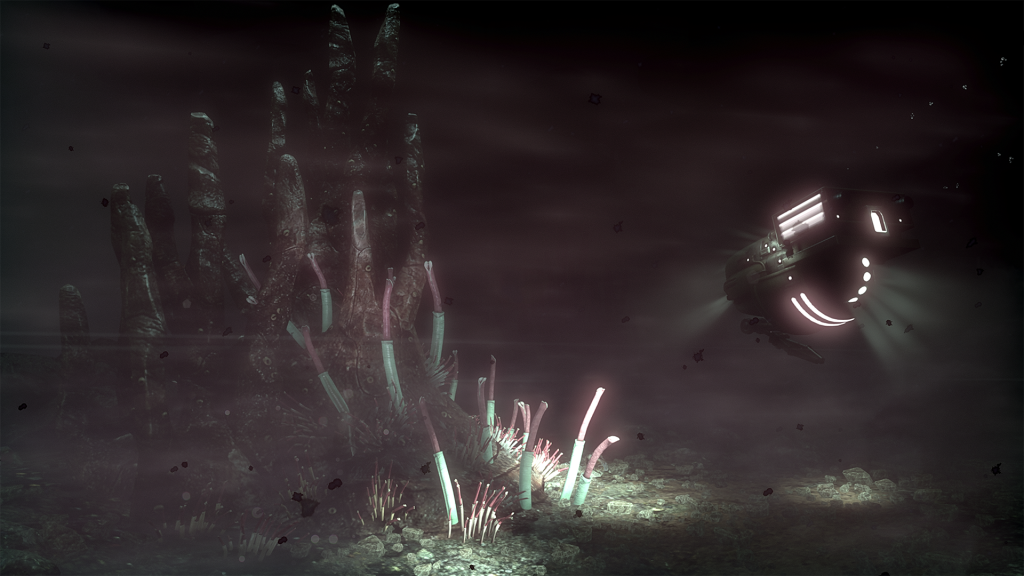

In SOMA you play Simon: a regular dude from 2015 Toronto, who— following a brain scan at the notoriously-disreputable York University— suddenly finds himself a hundred years in the future, just after a cometary impact has wiped out all life on the surface of the earth. Simon doesn’t have to worry about that, though— not in the short term, at least— because he’s not on the surface of the Earth. He’s stuck in a complex of derelict undersea habitats near a geothermal vent, where (among other things) he is attacked by giant mutant viperfish and caught up in a story centering around the nature of consciousness. “I’d really like to know who thought sending a Canadian to the bottom of the sea was a good idea,” he blurts out at one point. “I miss Toronto. In Toronto I knew who I was.”

So yeah, I can see a certain Watts influence. Maybe even a bit of homage.

If I was feeling especially egotistical I could really push it. Those subway stations Simon cruises through on his way to York— not that far from where I used to live. His in-game buddy Catherine once mistakenly remarks that he comes from Vancouver, where I lived before that. Hell, if I wanted to pull out all the stops I could even point out that Jesus Christ’s Number Two Man (and the first of the popes) was called Simon Peter. Coincidence?

Yeah, probably. That last thing, anyway. Then again, any game whose major selling point was its Peter Watts references would be shooting for a pretty limited market. Fortunately, SOMA is more substantive. In fact, it may not be so much inspired by my writing (or Dick’s, or Egan’s, or Miéville’s) as we all are inspired by the same scary-cool stuff that underlies human existence. We’re all drinking from the same well, we all lie awake at night haunted by the same existential questions: how can meat possibly wake up? Where does subjective awareness come from? What is it like to be attacked by giant mutant viperfish at four thousand meters?

SOMA’s influences extend beyond the the usual list of authors you’ll find online (or quoted at the top of this post, for that matter). The biocancer that infests and reshapes everything from people to anglerfish seems more than a little reminiscent of the Melding Plague in Alistair Reynolds’ Revelation Space, for example. And while Simon’s belated discovery that he’s basically a digitized brain scan riding a corpse in a suit of armor might seem lifted directly from the Nanosuit in my Crysis 2 tie-in novel, I lifted that idea in turn from Richard Morgan’s game script.

So much for the parts SOMA cannibalized. How does it stitch them together?

For starters, the game is gorgeous to behold and insanely creepy to hear. The murk of the conshelf, the punctuated blackness of the abyss, the clanks and creaks of overstressed hull plating just this side of implosion keep you awestruck and on-edge in equal measure. Of course, these days that’s true for pretty much any game worth reviewing (Alien: Isolation comes to mind— you might almost describe SOMA as an undersea Alien: Isolation with a neurophilosophy filling). SOMA’s technology seems strangely antiquated for the 22nd century — flickering fluorescent light tubes, seventies-era video cameras, desktop computers that look significantly less advanced than the latest offerings down at Staples— but that’s also true for a lot of games these days. (Alien: Isolation gets a pass on that because it was honoring the aesthetic of the movie. The Deus Ex franchise, not so much.)

There’s not much of an interface to interfere with the view, no hit points or health icons cluttering up the edges of your display. You know you’ve been injured when your vision blurs and you can’t run any more. You have no weapons to keep track of. The inventory option is a joke: for 90% of the game, you’re completely empty-handed except for a glorified door-opener to help you get around. It’s way more minimalist than most player interfaces, and the better for it.

Likewise, dialog options are pretty much nonexistent. Now and then you can choose to start a conversation, but from that point on you’re essentially listening to a radio play. I think Frictional made the right choice here, too. All those clunky dialog menus that pop up in Fallout or Mass Effect— those same four or five options offered up time after time, regardless of context (Really? I want to ask Piper about our relationship now?)— offer just enough conversational flexibility to really drive home how little conversational flexibility you have. It’s one of the inherent weaknesses of computer games as an art form— game tech just isn’t advanced enough to improvise decent dialog on the fly.

SOMA cuts the player out of the loop entirely during the talky bits. The cost is that we lose the illusion of control (which is actually kind of meta if you think about it); the benefit is that we get richer dialog, deeper characters, shock and tantrums and emotional investment to go along with the thought experiment. Simon isn’t some empty vessel for the player to pour themselves; he’s a living character in his own right.

I’ll grant that he’s not a very bright one. He mentions at one point that he used to work in a bookstore, but given how long it takes him to catch on to certain things I’m willing to bet that its SF and pop-science sections were pretty crappy. Simon’s a nice guy, and I really felt for him— but if his home town was, in fact, a nod to my own, I can only hope the same cannot be said for his intellect.

On the other hand, who’s to say I’d be any quicker on the draw if I was the dusty photocopy of a long-dead brain, thrown headlong and without warning into Apocalypse? I don’t know if anyone would be firing on all synapses under those conditions; and the languid pace at which Simon clues in does provide a convenient opportunity to hammer home certain philosophical issues to which a lot of players won’t have given much prior thought. The fact that Simon’s sidekick Catherine grows increasingly impatient with his “bullshit”, with the fact that she has to keep repeating herself, suggests that this was a deliberate decision on Frictional’s part.

But if Simon’s a bit slow on the uptake, SOMA isn’t. Even the scenery is smart. Wandering the seabed, at depths ranging from a few hundred meters to four thousand, the fauna just looks right: spider crabs, rattails, tiny bioluminescent squid and tube worms and iridescent, gorgeous ctenophores (ctenophores! How many of you even know what those are?) Inside one of the habitats, a dead scientist’s lab notes remark upon the sighting of a Chauliodus (“viperfish” to you yokels): “Not usually found at this depth— anomaly”. I wet myself a little when I read that. Writing Starfish back in the nineties, I too had to grapple with the fact that viperfish don’t foray into the deep abyss. I had to come up with my own explanation for why they did so at Channer Vent.

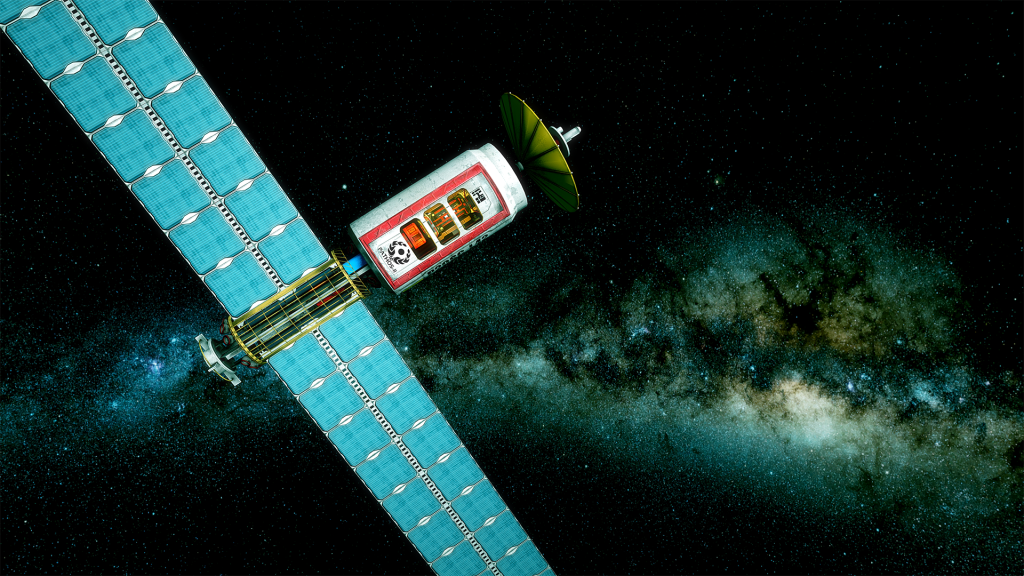

Smart or dumb, though, the ocean floor is mere setting: SOMA’s story revolves around issues of consciousness. Frictional did their homework here too. Sure, there’s the usual throwaway stuff— one model of sapience-compatible drone is dubbed “Qualia-class”— but stuff like the Body Transfer and Rubber Hand Illusions aren’t just name-checked; they actively inform vital elements of the plot. People come equipped with “black boxes” in their brains that can be forensically data-mined post-mortem. (This proves useful in figuring out SOMA’s backstory, an ingenious new twist on the usual Let’s find personal diaries lying around everywhere more commonly employed in such games.) Most of the lynchpin events in this story occur not to effect the course of the plot, but to make you think about its underlying themes.

By way of comparison, look to SOMA’s spiritual cousin, Bioshock. For all its explicit in-your-face references to Ayn-Randian ideology, Bioshock fails as analysis. (At best, its analysis amounts to Objectivism is bad because when capitalism runs amok, genetically-engineered nudibranchs will result in widespread insanity and the ability to shoot live bees out of your hands.) Andrew Ryan’s political beliefs serve as mere backdrop to the action, and as wall-paper rationale for the setting; but the events of the story could have just as easily gone down in a failed socialist utopia as a capitalist one. Bioshock was brilliant in the way it used the mechanics of game play to inform one of its themes (I’ve yet to see its equal in that regard), but that particular theme revolved around the existence of free will, with no substantive connection to Objectivist ideology. SOMA, in contrast, actually grapples with the issues it presents; it makes them part of the plot.

In fact, you could argue that SOMA is actually more rumination than game, an extended scenario that systematically builds a case towards an inevitable, nihilistic conclusion (two nihilistic conclusions actually, the second superficially brighter and happier than the first but actually way more depressing if you stop to think about it). If there’s a problem with this game, it’s that the the story is so tight, the rumination so railbound, that it can’t afford to give the player much freedom for fear they’ll screw up the scenario. There’s really only one way to play SOMA. Discoveries and revelations have to happen in a specific order, conversations must proceed in a certain way. The obligatory monsters— justified as failed prototypes, built by an AI trying to create Humanity 2.0— don’t really do anything story-wise. You can’t kill them. You can’t talk to them. You can’t scavenge their carcasses for booty, or fashion a makeshift cannon from local leftovers and blow them away. Your interactive options consist exclusively of run and hide. SOMA’s monsters serve no real purpose except to creep you out, and slow your progress along a narrative monorail.

There are choices to be made— surprisingly affecting ones— but they don’t affect the outcome of the plot. Your reaction to the last surviving human— wasting away in some flickering half-lit locker at the bottom of the sea, IV needle festering in her arm, pictures of her beloved Greenland (gone now, along with everything else) scattered across the deck— who only wants to die. The repeated activation and interrogation of an increasingly panicky being who doesn’t know he’s digitized (although he sure as shit knows something‘s wrong), a being you simply discard once you have what you need from him. The treatment of your own earlier iterations, still inconveniently extant after your transcription into a new host. These powerful moments exist not so much to further the story as to inspire reflection upon a story already decided— and they might be missed entirely by a player with too much freedom, able to go where they will and when. It’s the age-old tension between sandbox and narrative, autonomy and storytelling. Frictional has sacrificed one for the other, so— as immersive as this game is— it’s bound to suck at replay value.

It’s easy enough to justify such creative decisions in principle; in practise, the result sometimes feels like a cheat. I spent half an hour tromping around the seabed looking for a particular item among the wreckage— a computer chip— that would spare me the need to kill a sapient drone for the same vital part. It would have been easy enough for Frictional to give me that option; they’d already littered the seabed with wrecked drones, it wouldn’t have killed them to leave me some usable salvage. But no. The the only way forward was to slaughter an innocent being. It made the point, philosophically, but it felt wrong somehow. Forced.

This would normally be the point at which I bitch and moan about how, for all the “inspiration” game developers attribute to me, it would be really nice if they might someday be inspired to actually hire me instead of just mining my stories. It would be an utterly bullshit whinge— I’ve admitted to gaming gigs in my past on this very post— but I’d make it anyway because, Hey: if one of your inspirations is sitting right there in the corner next to the potted philodendron, why not ask him for a dance? He might just teach you a couple of new steps.[1]

This time, though, I’m going to restrain myself. SOMA could not have been an easy assignment; I could bitch about the monorail gameplay constraints or the intermittent dimness of the protagonist, but given the limitations of the medium I don’t know that I could do any better without compromising mission priorities. SOMA is a game in the straight-up survival-horror mode, but the horror is more existential than visceral. And those conventional mechanics serve the most substantive theme I’ve ever encountered in a video game.

Bottom line, I think they did a damn fine job.

[1] This metaphor is in no way meant to imply that I am any kind of dancer. My most recent memories of dancing involve jumping wildly up and down and slapping my thighs in approximate time to Money for Nothing.

I agree with your love of SOMA’s themes and story (and I honestly think they did choice in that game better than almost any other game I ever played simply due to how it has no bullshit “karma meter” going on) but I really wish it had the same gameplay as a good Bioshock or system shock game. They really allow for a lot of freedom in how you approach and tackle issues and the addition of combat would definitively make SOMA a harder game.

Despite that though it is tied with Bioshock Infinite and Technobabylon for the title of my favorite game of the past 5 years.

I (and the friend whom I played it with) loved the game. It has its flaws, as you point out, but it felt refreshing and different and the setting was wonderfully creepy.

Our main gripe would be the monsters, they felt forced and after a while less creepy because it became repetitive running and hiding from them. Same old, same old…

And have to note that we both felt that the game could have skipped the last scene, the one after the credits started. We feel the game would have felt more poignant had we not been given a scene abord the Ark. Just leave the player with despair and a little hope that it worked. Now it felt a bit to sugary sweet. We don’t always need a happy Hollywood ending.

Peter: So glad you wrote about this game. Couldn’t help comparing it to your work and Greg Egan’s!

Rex: It’s not a happy ending, as Peter alluded to in the article. The ARK is not hopeful. It is a dead end, a digital tombstone for humanity. The zoom out from the fake digital paradise to the ARK itself and then to the ARK in the context of the stars tells you all you need to know.

You could argue that the WAU was ultimately a better option for preserving humanity. It created robot Simon, which was a success.

I’m really happy you’ve gotten around to it, props to whoever sent it to you.

@Jason Robo Simon was not a success, because the WAU could not control the actions of the remaining humans and mockingbirds as they tore apart the facility in their death-throes. One of the themes of SOMA was entropy: everything was falling apart, everything was running off borrowed time as the supply line to the surface was severed. The WAU could not reverse that, it could use structure gel to plug leaks, but it is not some kind of miracle self-replicating nanomaterial. At most, the WAU could evolve novel functions (reminiscent of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolved_antenna).

There was a chance, but just like the asteroid diversion mission failed, the downside humans and the WAU did not have a unified plan to maintain self-sufficiency. The best they could do was the ARK, but even that would be doomed as micrometeorites slowly degraded its performance. The pure nihilism of this story is what stands out to me the most, the our existence is like a soap bubble that can be popped at any time.

I too wish someone would hire you to write a game.

Haven’t played it yet, but could Simon be simple because his copy is low rez, like i-tunes in the early years?

Sounds like an intriguing game…

Peter and everyone – on the extreme off chance you haven’t seen Black Mirror yet, I highly recommend giving it a watch (all episodes are on Netflix). Think of it as a darker, more pessimistic version of The Twilight Zone.

The most recent season in particular had a few themes in common with Echopraxia, which I had just finished (“Heaven” and the “zombie” soldiers each get their own episodes) so I had to rush in with my mostly unrelated post.

Enjoy!

you went on an acid trip?

I for one would like to hear about the acid trip.

As for SOMA, I liked it very much but as noted above, the ending is far from happy. The people on ARC are now completely isolated from any resources (even if they could somehow manipulate the outside of the ARC), subject to hard radiation and dust impacts. They would be better off staying at the station but even there they would be doomed. RTGs run out of juice in mere decades and then its light out.

then again, it might be that subective time for them is a year to an hour of real time.

It’s on sale this weekend for 60% off

https://www.gog.com/game/soma

http://store.steampowered.com/app/282140/

saw it in a GoG newsletter and remembered this post in case someone wants to check it out.

Why don’t you write your own pencil-and-paper roleplaying game?

I’d buy it.

I’m really here to ask why Siri Keeton’s dad’s name is Moore. Spy craft?

But this is my first Wattsian communication, so: Thanks for all the freebies, Dr. Watts! I was going to say that you, Gibson and Sterling are the brightest lights of our generation. Then I remembered what I paid to read you vs. the competition, and you catapulted into first place.

Here’s a dumber question (I’m high): I think Blindsight takes place some time (decades?) after Behemoth? If both series are in the same fictive universe, then I must say that N’am survived the Behemoth events better than I’d thought, and/or flourished in the time between ‘moth and ‘sight. Either that, or Siri was a spoiled rich kid? His childhood environment struck my as fairly nonpostapocalyptic.?.

Oh, and I fantasize about seeing you in a panel discussion with Sam Harris and maybe Neil Degrasse Tyson. It’d be like The Hardy Boys Meet Ian Anderson.

Ever read Spook by Bruce Sterling? Story could fit seamlessly into the Blindverse…

‘following a brain scan at the notoriously-disreputable York University’

Are you describing the game here or real life?

I’m seconding the Anon. I’d buy anything pencil-and-paper you produced. I’d even pitch money into a kickstarter for a modest-graphics game pitch where you do all the writing (even though I believe kickstarters are 99% scams).

For what it’s worth, I absolutey agree with Xirnium and the Anon before him. Personally a big fan of tabletop, vidya, and just about everything you’ve written. I’d absolutely buy any such thing you made purely for the influences of your writing, let alone gameplay (which I trust would be grand).

On a similar note, of countless authors and intellectual minds, I’ve found you’ve best achieved that ideal of balance, where you sacrifice neither scientific plausibility nor philosophical question.

Your shit’s hard as diamonds and no less pretty.

So should my comment be of any worth, do realize that a game of your cailber, in any format, would be a great breath of fresh air into the ever stagnant worlds of tabletop or video gaming.

Again (and to be fair) it’s happened a few times; it’s just that none of those projects ever led to a finished project.

Still. Hope springs eternal.

That’s a cool thought— and it would actually be more consistent with the level of brain-scan tech available in 2015 (though it would still remain a stretch)— but if there were any in-game clues pointing to that interpretation, I didn’t pick up on them.

Loved the first two seasons (with one minor exception). I’m a bit afraid to watch the third because apparently it’s been relocated to the states and retooled for American audiences; there’ve been some mixed reviews of the result. Still, I fully intend to check it out. (The problem is The BUG, who keeps saying she wants to watch all these too, so I have to wait until we’re both free— but then we just ending up watching another episode of some murder procedural instead. I’ll probably never even get around to Luke Cage either, at this rate…)

Not exactly. The stuff had expired. But PharmaSave refunded my money and gave me a couple new tabs, so I hope to have something to report soon.

Nah. Someone won a contest she entered to support a library somewhere; one of the prizes was being able to name a character in Blindsight. I think she picked her husband.

You’re more than welcome. And if I can toot my own martyr-horn for a moment, let me just point out that Tor recently offered to increase my backlist e-royalties (which, having been negotiated before the Big Five colluded on an “industry standard”, were crappy) to something less crappy— but only if I took down my freebie backlist page.

As you can see, said page is still online. So not only are you getting my words for free, it has actually cost me money to bring them to you. So, you know.

Adulate me.

Not dumb at all. (In fact, I’m guessing you’re one of not-that-many-people who might have noticed the tie-in.) But no: Rifters and The Consciousnundrum take place in separate timelines.

Parallel ones, though. For example, both timelines contained a Ken Lubin who went into the military. So I’m guessing the paths forked sometime after his early childhood.

Of course your comment has worth. I never turn down praise.

Of course, it would be worth more if you owned Bethesda, or something…

Okay, it was just a cheap shot. I know someone at York.

Haven’t seen the first two seasons of Black Mirror, but I’ve watched 5/6 of the third after reading Andrew’s comment, and love it.

Peter Watts,

Wondered about this as well. Jim Moore is an uncle’s name, the one most often compared with John Wayne.

But wonder if Mark is asking why Moore has a son named Keeton. Mommy issues I’d always assumed, given the Bondfast Formula IV and other factors such as possibly breaking the tradition of surnames coming from the male progenitor in Teh Fyuchurrs.

That last thing. I’m assuming matrilineal surnames, on the grounds that there’s rarely any doubt who the mother in. Also mDNA continuity.

I think you might also enjoy The Swapper.

It is not hard SF, but the material on consciousness is solid. The aesthetic and ambience are great. And is very polished.

Instead of hiding and running from mutated monsters, the gameplay consist of solving puzzles, which revolve its unique cloning mechanic.

It’s three bucks on Steam, during the current sale.

Peter Watts,

Holy fuck that’s brilliant.

(BTW I actually bought The Colonel on Amazon Prime when it came out, please add to my brownie point balance.)

Ironically that ties right in with the thought “I” just had that brought “me” back here now: Watts is all self-deprecating about his character development. However, having read the back-list to present,

I think we’d all agree that there’s a clear development in Watts’ skill at rendering 3D characters. I’d give him an arc probably better than, say, Larry Niven. Beyond that, the Behemoth trilogy opens with characters with profound psychological aberrations; and characters with children and day jobs as soulless corporate cogs. Frankly, I think Watts did a fantastic job of making those people believable and yet relate-able.

Imagine Watts is Siri Keeton. The development of Achilles Desjardin, Jukka and Valerie and company may be unique in making cutting edge brain science research into recognizably human characters (Watts’ feline credentials show here). Bonding a Taka Oulette to a largely rationalist atheistic readership is itself a writerly feat. Khan Noonian Singh bitched about stalled human evolution, Blindsight uses everything we’ve learned since Sterling wrote Schismatrix.

I’ve reread the B (Rifters?) trilogy, then most recently ‘sight. Rereading “praxia now. If I recall right, it had a happier ending for posthumanity than the Lovecraftian repute suggests. (Another author whose characters get rochambeaued by Watts’). Like H.P. though, Watts took on the challenge of peopling his novels with entities who are by definition smarter, more complex, more functional than our present species. Here, Watts recaptures the wonder of reading Neuromancer for the first time.

By the future time we reach in Echopraxia, Watts’ biologist credentials show their true worth. Heaven and hives and golem notwithstanding, human relations remain primate.

Up to ep 6 of Fortitude btw. Seires started strong, turned to a slog, getting interesting again…

For those who haven’t read The Colonel-

Jim Moore is of a brand of decision-maker that has existed since at least Sun Tzu and been mass produced since at least WW1. The Colonel gives us a peek at a future when Powers That Be would plausibly choose extinct-humanoid-predators as an improvement. It gives background for Moore’s ethical position that “we do not kill cat’s paws”. It’s an essential prologue that gets Moore to Echopraxia’s monastery.

The novella has other praiseworthy features, but I remember those offhand. Been a while since I read the bugger.

Mark Major,

“making cutting edge brain science research into recognizably human characters”… One of the things that’s bugged me about a lot of science fiction is it either assumed we’ll retain our human form in otherwise highly technological societies (ftl drives, anti-grav, teleportation, etc.), or attempted to write from a truly posthuman perspective, which for a non-posthuman like myself made it somewhat less engaging on a character-driven level. Watts somehow manages to create future worlds that seem plausible, given our current trajectory, with characters that are contextually realistic without being incomprehensible.

“the wonder of reading Neuromancer for the first time” … bought it summer ’84 off a book rack at a Greyhound stop somewhere east of the Peg … hadn’t heard of Gibson, didn’t understand half of it, but it blew my mind (half an orange phoenix probably contributed to the latter conditions, but it held up on second reading…)… still have that book, looking a little the worse for wear…

If you wonder why there’s been so much technical advance, but the human form in general hasn’t changed all that much, check his timeline. The stuff happening in the “blindopraxia” timeline is not quite a century from now. This is huge amounts of time in the increasingly compressed and rapid generations of advance in things like computing technology, media, and the like. For living things the size of humans, many less generations and less time to adapt. We see massively advanced technology and relatively unchanged humans being integrated, Siri etc is far from alone but outside of implants for medication dispensing or media participation, most humans seem to be essentially not modified or not modified much. The exceptions seem to be humans who have taken deep modification to themselves since becoming adults, or people for whom modification as pre-adult was a medical necessity (again, Siri). One of the glaring exceptions to the rule is the existence of Valerie and her ilk, though they are a very small population and not exactly intentionally released into the wild to interact with the general public gene-pool. I don’t recall, offhand, any of these being depicted as being as modified as, say, Rifters, “zombies”, hive-minded, etc.

All of this being said, I have no idea how Peter Watts manages to depict some of his characters as being “reasonable” in their context; I have a hard time understanding “kids these days” as being reasonable in the context of lives growing up under social media and with a cellphone/tablet in their hands since before they could read. Yet he does manage to pull it off and for me this only adds to the sense of wonder.

Think Black Mirror S3 is worth checking out if only due to subjects involved. S3E4 has VR “heaven” for example. And not all eps are pure USian.

Quote from Catherine, when Simon asks if the scans for the Ark are similar to his: “No, yours is flatter, if that makes sense, less dynamic”.

Plus, he has brain damage – that’s why he had his brain scanned in the first place.

In the case of being forced to kill a sapient drone for it’s circuitry, I too felt it was overly forced on my first playthrough.

Upon playing through a second time however, it turned out that this akward moment was actually yet another moral dilemma / thought experiment in disguise.

You have the choice of murdering either the useless but self-aware drone imprinted with Brandon Wan, or the friendly helper bot who has been following you around like a puppy, unwelding doors and illuminating your surroundings for you.

You played it twice? How was it the second time? Was I off-base about the whole sucky-replay-value thing?

I’ve played this game through three and ongoing times. A lot of that is due to the environment, which creeps me out in just the right way. But also, I do actually enjoy that the PC is a fucking moron. It puts shit onto the player, which is kinda rare and sorta sweet.

On the subject of the time-split, there used to be a diagram explaining this. Still lives at http://rifters.com/old-index.htm – I saw this before I had read past *Starfish*, which may be why I was never confused.

“it would be really nice if they might someday be inspired to actually hire me”

Name your price, Peter. I bet many of your indie dev fans would love to add your work to their projects but are essentially broke (like me)

Then again, your name on the credits would bring at least 10 people to back the Kickstarter…

Peter Watts,

Well, it might be worth for some just to see short results of the binary choices you have to make throughout the story, to ponder about them. That’s besides playing again to find new stuff you may possibly missed on first walkthrough, since game is basically a “find all the lore scattered around the game”.

Maybe a bit late, but here’s some complementary stuff to the game, that was released prior to em… release of a game, as a sort of promo material. Can serve as an additional insight even after finishing the game.

http://somagame.com/files.html

Thomas Hurst,

All scans are flat by default, WAU and Cath had to copy each others results to bring scans to “life”. It’s talked about in the game + Vivarium trivia, so i’m not gonna go derailing into details unless you want to.

James Nova,

It’s a scan of Javid Goya, another wrangler from Delta.