Fruit Flies, Freeloaders, free will.

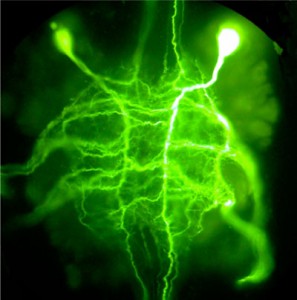

For the past few months an image has been itching at the back of my mind, like a piece of grit waiting for a story to accrete around it: a neuron culture in a petri dish, like a rifters head cheese but without any inputs to keep it sparking. We presume that all internal feedback loops have cycled to extinction, and that quantum effects are either suppressed or accounted for. We presume, for the sake of the scenario, that no inputs exceed action potential — that these ultimately reactive cells, capable of relaying signals but not generating them, are starved for any physical stimulus that might provoke them into firing.

We presume that they are firing anyway — and the label etched on the glass in fine-tipped Sharpie reads

Free Will — Sole Confirmed Instance

I originally envisioned this as a short-short for Henry Gee’s “Futures” series in Nature, but I couldn’t come up with a punchline that worked. At this point it’s probably going to end up as a brief scene in the first Sunflowers story — but either way, I seem to have been scooped by reality.

Which is my way of saying I might have to rethink this whole no-Free-Will thing I’ve been pimping since forever.

Of course, Free Will in its purest, Coke Classic form is bullshit pretty much by definition. Neither the deterministic rules of cause-and-effect nor the random fluctuations of quantum uncertainty leave free-will wiggle room for any purely physical entity: all we do and all we are ultimately traces back to external factors over which we have no control, an infinite-regress of buck-passing reaching all the way to the Big Bang. The only way we can be truly autonomous in a physical environment is if some part of us is not physical, if ghosts really do inhabit these machines. Free Will — the pure uncut stuff, upon which societies and legal systems have been based since the dawn of history —is a duallist delusion. It’s not even worth debating.

Which makes me kind of a doofus for debating it all these years.

I’m beginning to think that my endless ridicule of that antiquated concept has blinded me to more useful definitions — less pure in the concept, more restrictive, but perhaps with real functional utility. It’s been argued, for example, that natural selection would give rise to something like free will, since purely deterministic behavior would leave you predictable, and hence vulnerable to predators. It’s easy enough to demolish that argument: You don’t need free will, you just need deterministic processes too complex for the predator to predict, or You could make yourself unpredictable by just throwing in some arbitrary random behaviors, but being slaved to a dice roll nets you no more freedom than being slaved to a flow chart. But that’s the old mind set, that’s Free Will Classic. There comes a point past which deterministic processes grow too complex to predict at any given state of the art, a point at which determinism becomes functionally indistinguishable from free will. Past that point, what difference does it make whether we are driven by algorithm or ectoplasm? It all looks the same; it all interacts the same with the rest of the universe. And nature, as I pointed out with such glee in Blindsight, doesn’t give a damn about motives. It only cares about outcomes. A difference which makes no difference is no difference[1].

So I’ve been reading some of the claims put out by the FreeWillians: Aping Mankind: Neuromania, Darwinitis, and the Misrepresentation of Humanity for one, written by a cranky ex-geriatrician and neuroscientist named Tallis, out of Manchester. The dude takes a dim view of mechanists in general and “neuromaniacs” in particular. We are not just mammals with big brains, he claims, and Free Will does exist — and as far as I can tell he’s talking about the Coke Classic variety (capitalized here, to distinguish from the more mundane faux “free will” of complex determinism). What’s especially intriguing is that Tallis claims to be staunch atheist with no time for dualism or vitalism or any of the other isms that Free Will seems to hinge on. I have no idea how he’s ultimately going to make his case. I’m only a third of the way in, and so far he’s mostly just characterized modern neurology as phrenology in sheep’s clothing. But he knows the field, and — despite an unhealthy fondness for straw men — he’s managed to anticipate most of the counterpoints someone like me would raise. Apparently he explains consciousness in the last half of the book, which should be a neat trick given that he’s already dismissed both spiritual and mechanical toolboxes.

Then you’ve got the works of Giulio Tononi out of the Neurosciences Institute, who has apparently concluded that consciousness is an intrinsic property of all matter, like charge and mass. I’ve heard this before, and it’s always struck me as way too close to the woo-woo end of the scale, but apparently there’s some mathematical justification for it. Again, I haven’t reached those papers yet; I’m still digging around in Tononi’s publications from the nineties, which muck around mainly with synchronized distributed neural firing as a correlate of consciousness. But again, I can’t wait to see how it turns out.

And then there’s this 2011 paper by Brembs in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: “Towards a scientific concept of free will as a biological trait: spontaneous actions and decision-making in invertebrates.“[2]

Let me just emphasize that.

Free will.

In invertebrates.

We’re not just talking about sexy brainy cephalopods, either; Brembs would extend free will even unto cockroaches. He believes it arises from the fact that “animals need to balance the effectiveness and efficiency of their behaviours with just enough variability to spare them from being predictable.” So he starts with the usual dice roll in the cause of predator avoidance— but he ends up in a broader world where exploration of the unknown is better served by initiative than by rote response. He cites other studies — behavioral, neurological — suggesting that while determinism may be fixed and dice rolls may be stochastic, you get something more adaptive than either when you put them together:

“Much like evolution itself, a scientific concept of free will comes to lie between chance and necessity, with mechanisms incorporating both randomness and lawfulness. … Evolution has shaped our brains to implement ‘stochasticity’ in a controlled way, injecting variability ‘at will’.”

Not Free Will, but free will.

Brembs describes ancient studies on fruit flies, in which a constant percentage of the population performed a conditioned response to a stimulus but that percentage consisted of different individuals from trial to trial — as if every fly knew the drill, but would simply decide to “sit this one out” every now and then. He cites Searle and Libet and Koch (Koch — another guy I’ve got to read), argues that a concept of “self” is essential to any force of “will”. He also admits that “Consciousness is not a necessary prerequisite for a scientific concept of free will”. (Whew.) He waxes metaphysical and mechanist and even semantic, addressing the question of why we’d even want to retain the term “free will” when it comes with so much baggage, and the phenomenon he’s pimping is much more circumscribed: wouldn’t “volition” be better? (Short answer: no.)

| But for all the far ranges of Brembs’ discussion, and for all the studies he draws into that net, one sticks in my mind above all others: the nervous system of a leech, cut from its corpus and kept alive in splendid isolation. No inputs; hell, no sensory organs to provide inputs. Just an invariant current in an impoverished sensory void; yet even here that isolated network somehow made decisions, told non-existent muscles to swim or to crawl, depending on—

Well, we don’t know, do we? It’s hard to imagine a biological scenario in which conditions could be more static.

It’s my isolated head cheese in a petri dish. It’s my Free Will — Sole Confirmed Instance. Only it’s real. For the moment, the only fresh insight I might offer up is one of perspective. If free will really did arise as a way of keeping us safely unpredictable in a hostile universe — and if it is just an adaptive combination of dice and determinism — then it resides outside the organism: not within us, but within the things that watch us. If unpredictability makes us free, then we become slaves to anything that calls our next move. Think of it as a kind of metaphysical Observer Effect. The Plecostomus down in my aquarium may be a free agent now, with naught but the glassy stares of tetras and gouramis to keep him in line; but the moment I’m line-of-sight his autonomy-wave collapses down to automaton. |

Of course, given that it’s tough enough to swat a black fly when he’s really on his game, a little unpredictability seems to buy a whole lot of freedom. So I’ll keep working through the mountain, digging through papers by Tononi and tracts by Tallis. I’m not yet convinced these arguments are valid; but then again, I’m not convinced they aren’t.

And what’s so exciting — after spinning my wheels all this time — is that at long last, the argument seems worth having again.

[1] I would give points to anyone who could ID the source of this formerly-obscure quote, but Google has long since stripped away any challenge from the Human adventure.

[2] And sincere thanks to whoever pointed me to this and other papers; it was either in an email or a facebook link but I can’t find the fucking source anywhere and it’s driving me crazy.

Warning: file_put_contents(): Only -1 of 21106 bytes written, possibly out of free disk space in /var/www/virtual/rifters.com/htdocs/crawl/wp-content/plugins/wpdiscuz/utils/class.WpdiscuzCache.php on line 165

Paragraph beginning “I’m beginning to think…”, sentence beginning, “There comes a point…”, “becomes TO complex to…”.

Otherwise, there are always possibilities.

Actually, I’m out of my depth to the point I don’t even have a pattern to throw at it. 🙂 Is the leech hallucinating? Phantom input, like phantom pain for lost limbs? Faaaaascinating…

Thank you Peter, this kind of crunchy philosophical neuro talk is just what my brain needed to sink its metaphorical teeth into right now. Mmm, crunchy.

Can’t help but think that you will be disappointed by the last half of that free-will argument; I haven’t read that book (or even heard about the guy) but logic seems to always go out the window when people feel strongly enough that something just *ought* to be true – so I’ll bet a beer that something suspiciously similar to a soul, under a different name, will be the resolution of the puzzle in the end. (Or maybe “because quantum!!”, that one is always popular.)

On second thought, I’ll gladly buy you a beer regardless when you come to Uppsala, so never mind.

I wonder, how does the “complex determinism” flavor free will line up with that idea that brains operate in the no mans land between order and chaos? Do perhaps all useful networks just naturally end up in the unpredictable region between noise and regularity? (Or is that idea just BS too? I’ve really only seen the oversimplified New Scientist style article here; and haven’t been looking too hard for the serious, impenetrable writing kind of treatment.)

This is just a bit creepy. Definitely another step closer to making a zombie.

I’d love to know what the hell is keeping that leech’s nervous system busy even after the rest of the animal is gone.

I don’t know if the difference between invert and vertebrate bodies might contribute to the activity going on there. I’d think an animal like a leech has alot more muscle contractions going on than most vertebrates. That with the knowledge that a leech’s body is fairly simple compared to a mammal, I’d wonder if there isn’t some kind of autonomy in that system that keeps going a little while before dying off.

Personally, I wouldn’t want to subject any higher animal to this experiment just for the sake of an argument. I’m as curious as the next person, but I just can’t see enough justification for doing that to an animal with a complex nervous system.

I’m not entirely sure a more complex system would survive as long as this one did. It would scare me if it did, but not because of any implication of what it might mean. I’d be worried about someone using stripped nervous systems in other scenarios.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verificationism

Would interactive computation provide a formalism for your thought experiment?

That is, imagine a little leech simulated by a Turing machine with a description of the leech’s current state on tape, some work tapes and an input tape that describes its current surroundings. At each step, some World process might alter the input tape. The leech TM reads some information from the input tape, alters the state of the leech, and maybe alters some part of the input too, if the simulated actions of the leech alter the environment.

Now cutting the nervous system out the leech would be analogous to permanently filling the input tape with blank symbols. Does the leech simulation now possess free will?

nb: I am a theoretical computer scientist, and when all you have’s a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

I’ve heard that ‘difference’ quote in the context of logical positivism. doing a search on that brought up the wiki page with a potential source cor you from William James.

“””

James’s exact words, in the essay “What Pragmatism Means” in his book Pragmatism (1907) are “There can be no difference anywhere that doesn’t make a difference elsewhere — no difference in abstract truth that doesn’t express itself in a difference in concrete fact and in conduct consequent upon that fact, imposed on somebody, somehow, somewhere and somewhen.”

“””

Kind of like a cockroach after you give it a headectomy, the leftovers just keep going for a few weeks until the energy reserves run out. Plus they don’t need a brain to breathe.

Could whatever nutrient solution they’re using to keep this thing alive be, I don’t know, stimulating it somehow? Providing enough juice to produce some basic neural activity without sensory input?

What does a brain “see” when it’s got nothing to “see” with?

Ghost in the machine is just an infinite regress – how does the ghost work? One needs rules to compute a mind, and it doesn’t matter if the rules are in physics-land or in woo-land, they have to be ultimately deterministic or truly random, and so why not assume per Occam’s Razor they are physical? Woo adds nothing. In practise it’s used as a marker indicating “beyond this point I want to believe my social instincts that evolved to consider agentish things as ontologically basic, I don’t want to try to pick apart how the agent works”.

In my opinion what the words “free will” usefully mean, is that a problem is too under-specified for any formulaic solution, and so an agent must use heuristic methods to narrow the search. That means that the chosen methodology to solve the problem is not determined BY the problem. More than one method can work. The ur-search is a drunkard’s walk. Anything more complex merely improves on that.

And that’s what this is: a drunkard’s walk. The leech can get by solving its heuristic problems randomly, and so it does.

“…Yet, under these ‘carefully controlled experimental circumstances, the animal behaves as it damned well pleases’”

How refreshing to see that the Harvard Law of Animal Behaviour is still observed.

Someone recently summarized my objection to the illuson of consciousness by asking “if consciousness is an illusion, then who is being fooled” (Other people, I guess). I’m a believer in lower case free will along the same lines, the term “illusory” loses it’s meaning when referring to internal states. I am sad, but this is an illusion? I am confused, but this is an illusion?

As for the cut off nervous system, maybe it’s being stimulated by cosmic rays (Terry Pratchett has a nice riff on this with his inspiration particles that create ideas when a receptive brain is hit on the right spot)

Consciousness is you applying your social prediction instincts to yourself, modeling yourself as an ontologically basic agent just like it models other people, and largely based on interpreting cues rather than honest privileged information. Its primary function is the selective inhibition of gaffes.

Great discussion! Here’s my take on it:

A neuron, even when its membrane potential is close to its resting value, is never resting. The ion pumps keep going. It is an active dynamical system subject to noise that can be driven to fire in the absence of sensory stimuli.

There are some types of neurons that just won’t shut up, such as these hypothalamic circadian rhythm neurons. Disconnect them from any other neuron and they still fire spontaneously at 2-3 Hz sixteen hours a day (figure 2). I would argue that they have no more free will that any other system cut from external input but fed enough energy to keep going (e.g., a wristwatch); their behavior being richer, more unpredictable than that of static systems (say, a rock sitting on the ground) simply because they amplify noise in their medium better.

Independence from sensor input and motor output is not true isolation. A nervous systems takes space, has a temperature and possesses a programming tuned to the presence of a body. Even if the driving force of its dynamics reside close to it (fluctuations of temperature or of ionic concentrations outside the membrane of its neurons), they’re not under its control; they are no more endogenous than external retinal input to the visual cortex simply because we don’t assign a meaning to them. If we could strip away all that variability, we would be left we something akin to a deterministic simulation, future dependent only on the current state of the system.

As a side note (since we are discussing neural dynamics in the absence of sensory stimulus) if any of you is coming to the Magdeburg resting-state brain connectivity conference, we could get together and have a beer.

Interesting stuff.

One thing I always keep in mind is that at this level biological systems are not much more than really complicated chemical mixtures, which automatically means that they can show unintuitive effects. Even before considering what the structures do in their own environment. I think I am still influenced by reading Stuart Kauffman all those years ago.

Simple chemical systems chemical systems can already show oscillating behaviour without any external input. Which could be similar to what happens in the isolated nervous system. Especially because as far as I know these systems already exist at the edge of stability, and are optimized to boost small differences in signal.

One source for the initial fluctuations that result in the generation of these patterns in the isolated nervous system could be the inherent properties of enzymes involved. There is some indication enzymes naturally cycle between different conformations, some of which are active, some of which are inactive.

…then what made John Kerry drive his swift boat directly at a firing enemy on the bank of the waterway he patrolled, the first time?

And when answering this for yourself, try hard to factor in the fatalism surrounding seeing the effects of flying projectiles hitting your coworkers and your boat. (I’m not trying to throw any patriotic guilt at you, I just think that a firefight is a unique and horrifying experience that we armchair quarterbacks can’t fathom.)

[…] horrifying!” rapidly crowds out “That’s true” in most discussions. However, this rates as the most interesting, nonobvious discussion of the topic I’ve run across in a while. […]

[…] Peter Watts on free will […]

Re: the quote… I didn’t look it up, but I remember long ago hearing the quote attributed to Spock, and liking it so much I always remembered it (and use it myself from time to time).

Quite interesting, although it still seems like the leech’s nervous system, by nature of however it’s built up (and yes, perhaps kept parlty because unpredictability’s an evolutionary advantage), have some kind of “every once in a while, with the decay of some subatomic partical or something flip a bit and turn a 0 into a 1 or vice versa” quality that causes its neuron to fire even in the absence of input (new input, anyway).. That is, the leech isn’t “deciding” so much as just, sometimes, randomly doing stuff because it’s that’s how it’s built (in the non-consciousness-requiring way). After all, the leech’s nervous system isn’t receiving NO input… if it was, it’d be dead matter. The input may be invariant, but it’s not absent.

And anyway, even unpredictability on the microscopic scale doesn’t always translate to gross unpredictability. You might not know exactly which direction a cockroach is going to run, but you can be pretty sure that it will run when you’re moving towards it, and with humans, you can get a lot done just by predicting the macroscale… an AI wouldn’t have to know how every neuron in humanity is firing in order to know where most of us are going to be at any given time – it just has to have enough data to know our habits. (Which reminds me I once had a story fragment idea about human beings, paranoid at seemingly-omniscient AIs and other systems that were complex enough to predict human behavior reliably, getting implants that introduce true randomness into their decision-making… and before that, relying on things like dice rolls and such as fetishistic items they believed, more or less incorrectly, would keep them unpredictable).

A completely isolated quantum computational system could be perhaps said to temporarily maintain freewill, while it is ‘coherently’ mulling over any given problem or question- until it de-coheres to connect the i/o channel back to ‘reality’.Greg Egan explores this concept quite a bit in _Schild’s Ladder_. There are plenty of ways to problematize this. Temporality of any given computational substrate, for one: in any given time-horizon if the system is isolated then it might have free will [according to the rules implied by the above example- I’m not saying I completely buy this argument]- but once that horizon expands then poof, yer isolated pure computational substrate gets all contaminated. I like Thomas Pynchon’s sense of humor about this problem, in Crying of Lot 49. Cause that’s what it’s all about …

expert from Computer One by Warwick Collins(free will AI that can predict us because of our habits, nervous system in a AI super-network too)

‘Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, I thank you for

giving me at short notice the opportunity to express my views

on a matter of some small importance to me and, I hope, to

you. I shall begin by outlining some background to a theory,

and in due course attempt to indicate its application to

computers and to the future of humanity.

‘In the 1960s and early 1970s, a fierce academic battle

developed over the subject of the primary causes of human

aggression.

‘The conflict became polarised between two groups.

The first group, in which the ethologist Konrad Lorenz was

perhaps the most prominent, advocated that human aggression

was ”innate”, built into the nervous system. According

to this group, aggressive behaviour occurs as a result of evolutionary

selection, and derives naturally from a struggle for

survival in which it was advantageous, at least under certain

conditions, to be an aggressor. Lorenz was supported by a

variety of other academics, biologists and researchers. Interpreters,

such as Robert Ardrey, popularised the debate.

Lorenz’s classic work On Aggression was widely read.

‘Lorenz advocated that in numerous animal systems,

where aggressive behaviour was prevalent, “ritualisation”

behaviours developed which reduced the harmful effects of

aggression on the participants. In competition for mates, for

example, males engaged in trials of strength rather than

fights to the death. He suggested that a variety of structures,

from the antlers of deer to the enlarged claws of fiddler crabs,

had evolved to strengthen these ritualisations.

‘Lorenz argued that humans, too, are not immune from

an evolutionary selection process in which it is advantageous,

at certain times, to be aggressive. By recognising that

human beings are innately predisposed to aggressive acts,

Lorenz argued, we would be able to develop human ritualisations

which reduce the harmful affects of aggression by redirecting

the aggressive impulse into constructive channels.

If we do not recognise the evidence of aggression within

ourselves, Lorenz warned, then the likelihood is that our

aggression will express itself in far more primitive and

destructive forms.

‘Ranged against Lorenz were a group of sociologists,

social scientists and philosophers, often of a sincerely Marxist

persuasion, who advocated that humans are not “innately”

aggressive, but peaceable and well-meaning, and

that as such, humans only exhibit aggressive behaviour in

response to threatening stimuli in the environment. Remove

such stimuli, this group advocated, and humankind can live

peaceably together.

‘In reading about this debate in the journals, newspapers

and books that were available from the period, several

things struck me. I was impressed by the general reasonableness,

almost saintliness, of the aggression “innatists”, and equally surprised by the violent language, threats and authoritarian

behaviour of those who thought human beings

were inherently peaceful. Many of the advocates of the latter

school of thought felt that the opposing view, that aggression

was innate, was so wicked, so morally reprehensible, that its

advocates should be denied a public hearing.

‘Intellectually speaking, both positions were flawed,

and in many senses the argument was artificial, based upon

less than precise definitions of terms. But it engaged some

excellent minds on both sides, and it is fascinating to read

about such intense public debate on a central matter.

‘My own view involves a rejection of both of the two

positions outlined above. That is, I do not believe that

aggression is innate. At the same time, I do not think it is

“caused” by environmental factors; rather, some broader,

unifying principle is at work. The hypothesis I have developed

to explain the primary cause of human aggression is, I

submit, an exceptionally sinister one. I am fearful of its

implications, but I should like to challenge you, my tolerant

audience, to show me where the argument does not hold.

‘The main difficulty in the view that aggression is

innate, it is now agreed, is that no researcher has identified

the physical structures in the human nervous system which

generate “aggression”. There is no organ or node, no

complex of synapses which can be held to be singularly

causative of aggressive behaviour. If aggression emerges, it

emerges from the system like a ghost. What, then, might be

the nature of this ghost?

‘I propose to begin by specifying alternative structures

and behaviours which have been clearly identified and to

build from this to a general theory of aggression. Although

explicit aggressive structures have not been identified, it is

generally agreed that all organisms incorporate a variety of

defensive structures and behaviours. The immune system

which protects us from bacteriological and viral attack, the

adreno-cortical system which readies us for energetic action

in conditions of danger, are examples of sophisticated structures

which have evolved to respond defensively to outside

threats. Our mammalian temperature regulation system is

also, properly speaking, a defensive mechanism against

random shifts in temperature in the external environment. A

biological organism to a considerable extent may be characterised

as a bundle of defensive structures against a difficult

and often hostile environment.

‘Assuming that evolutionary organisms embody well

defined defensive mechanisms, what happens as their nervous

systems evolve towards greater complexity, greater

“intelligence”? This is a complex subject, but one thing is

plain. As nervous systems develop, they are able to perceive

at an earlier stage, and in greater detail, the implicit threats in

the complex environment. Perceiving such threats, they are

more able, and thus perhaps more likely, to take pre-emptive

action against those threats.

‘This “pre-emptive” behaviour against threats often

looks, to an outsider, very much like aggression. Indeed, it so

resembles aggression that perhaps we do not need a theory of

innate aggression to explain the majority of “aggressive”

behaviour we observe.

‘According to such an hypothesis, aggression is not

innate, but emerges as a result of the combination of natural

defensiveness and increasing neurological complexity or

”intelligence”. I have described this as a sinister theory, and I should like to stress that its sinister nature derives from the

fact that defensiveness and intelligence are both selected

independently in evolution, but their conjunction breeds a

perception of threats which is rather like paranoia. Given that

all biological organisms are defensive, the theory indicates

that the more “intelligent” examples are more likely to be

prone to that pre-emptive action which appears to an observer

to be aggressive.

‘The theory has a sinister dimension from a moral or

ethical point of view. Defence and intelligence are considered

to be morally good or at least neutral and are generally

approved. Wars are widely held to be morally justifiable if

defensive in nature. Intelligence is thought to be beneficial

when compared with its opposite. Yet behaviour resembling

aggression derives from the conjunction of these two beneficial

characteristics.

‘A physical analogy of the theory is perhaps useful.

The two main chemical constituents of the traditional explosive

nitroglycerine are chemically stable, but together they

form a chemically unstable combination, which is capable of

causing destruction. Evolution selects in favour of defensiveness,

and also in favour of increasing sophistication of

the nervous system to assess that environment. However, the

conjunction of these two things causes the equivalent of an

unexpected, emergent instability which we call aggression.

‘With this hypothesis, that defence plus intelligence

equals aggression, we are able to explain how aggression

may emerge from a system. But because it arises from the

conjunction of two other factors, we do not fall into the trap

of requiring a specific, identifiable, physical source of aggression.

We thus avoid the main pitfall of the Lorenzian

argument.’

Yakuda paused. It occurred to him how extraordinarily long-winded he sounded. He had tried to compress the theory

as much as possible, but at the same time he did not want to

leave out important background. The hall was silent for the

time being, and he felt at least that he had gained the

audience’s attention. Taking another breath, he pressed on.

‘ Scientific hypotheses, if they are to be useful, must be

able to make predictions about the world, and we should be

able to specify tests which in principle are capable of

corroborating or refuting a theory. Our theory proposes that,

if all biological organisms have defensive propensities in

order to survive, it is the more neurologically sophisticated

or “intelligent” ones in which pre-emptive defence or

“aggression” is likely to be higher. Accordingly, we would

expect the level of fatalities per capita due to conflict to be

greater amongst such species. There is considerable evidence

that this is the case.

‘One further example may suffice to indicate the very

powerful nature of the theory as a predictive mechanism.

Amongst insects, there is one order called Hymenoptera.

This order, which includes ants and bees, has a characteristic

”haploid-diploid” genetic structure which allows a number

of sterile female “workers” to be generated, each similar in

genetic structure. In evolutionary terms, helping a genetically

similar sister has the same value as helping oneself.

This means that large cooperative societies of closely related

female individuals can be formed. Such societies function

like superorganisms, with highly differentiated castes of

female workers, soldiers, and specialised breeders called

“queens”.

‘Clearly, a bee or ant society, often composed of many thousands of individuals, has far more nervous tissue than a

single component individual. With the formation of the

social organism, there is a quantum leap in “intelligence”.

I am not saying that the individual Hymenopteran is more

“intelligent” than a non-social insect. In practice, the amount

of nervous tissue present individually is about the same when

compared with a non-social insect. What I am saying is that

an advanced Hymenopteran society is vastly more “intelligent’

‘ than a single, non-socialised insect. With this in mind,

are the social Hymenoptera more “aggressive” than other

insects, as our theory predicts? The answer is perhaps best

extrapolated numerically. Amongst non-social insect species

deaths due to fights between insects of the same or

similar species are low, of the order of about 1 in 3000. The

vast majority of insect deaths are due to predators, the short

natural life-span, and assorted natural factors. By contrast, in

the highly social Hymenoptera, the average of deaths per

capita resulting from conflict is closer to 1 in 3. That is to say,

it is approximately 1000 times greater than in the nonsocialised

insects.

‘In ant societies in particular, which tend to be even

more highly socialised than wasps or bees, aggression

between neighbouring societies reaches extraordinary proportions.

The societies of a number of ant species appear to

be in an almost permanent state of war. The habit of raiding

the nests of other closely related species, killing their workers,

and making off with their eggs so that the eggs develop

into worker “slaves”, has led to the development of distinct

species of “slaver” ants whose societies are so dependent

upon killing the workers and stealing the young of others that

their own worker castes have atrophied and disappeared.

Such species literally cannot survive without stealing worker

slaves from closely related species. It should be stressed this

is not classical predatory behaviour. The raiding ants do not

eat the bodies of the workers they kill, or indeed the eggs they

steal. Accurately speaking, these are “aggressions”, that is

to say, massacres and thefts, not predations.

‘The need for conciseness in this paper limits anything

more than a brief reference to humans, in which the ramifications

of the theory generate a variety of insights and areas

of potential controversy. For example, in our ”justification”

of our own aggressive acts, human beings appear to express

an analogous structure to the general rule. The majority of

aggressions, if viewed from the aggressor societies, are

perceived and justified as defences. Typically, a society

“A” sees a society “B” as a threat and mobilises its

defences. Society B interprets A’s defensive mobilisation in

turn as a threat of aggression, and increases its own defensive

mobilisation. By means of a mutually exaggerating or leapfrogging

series of defensive manoeuvres, two societies are

capable of entering a pitched battle. We do not seem to

require a theory of innate aggression to explain much, if not

most, of the aggressive behaviour we observe.

‘This is the briefest outline of the theory, but perhaps

it will suffice as an introduction to what follows. Using the

theory, it is possible to make one very specific and precise

prediction about the rise of advanced computers, sometimes

called “artificial intelligence”, and the considerable inherent

dangers to human beings of this development in the

relatively near future.

‘Over the last seventy-five years approximately, since

the end of the Second World War, rapid progress was made not only in the complexity of computers, but in their linkage

or “interfacing”. In the course of the final decade of the

twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first, a

system of internationally connected computers began increasingly

to constitute a single collective network. This

network, viewed from a biological perspective, could with

accuracy be called a superorganism. Such a development

begins, in retrospect, to ring certain alarm bells.

‘If the increase in computer sophistication, both individually

and in terms of interfacing, results in a quantum

increase in the intelligence of the combined computer systems,

will the superorganism so formed begin to demonstrate

the corresponding increase of aggression exhibited by Hymenopteran

societies relative to less socialised insect species?

‘Clearly, since computers have not evolved by natural

selection, they are not programmed to survive by means of a

series of defensive mechanisms. This, it may be argued, is

surely the main saving factor which prevents computers

behaving like the products of evolutionary selection. However,

a parallel development is likely to produce an analogous

effect to self-defensiveness in the computer superorganism.

‘Over the course of the last few decades, computers

have increasingly controlled production, including the production

of other computers. If a computer breaks down, it is

organisationally effective if it analyses its own breakdown

and orders a self-repair. When a computer shows a fault on

its screen, it is practising self-diagnosis, and it is a short step

to communicating with another computer its requirement for

a replacement part or a re-programme.

‘Building instructions to self-repair into computers, an apparently innocuous development which has taken place

gradually, will have exactly the same effect on the superorganism

as an inbuilt capacity for self-defence in Darwinian

organisms. In other words, the intelligent mechanism will

begin to predict faults or dangers to it in the environment, and

act to pre-empt them.

‘A highly developed, self-repairing artificial intelligence

system cannot but perceive human beings as a rival

intelligence, and as a potential threat to its perpetuation and

extension. Humans are the only elements in the environment

which, by switching off the computer network, are capable

of impeding or halting the network’s future advance. If this

is the case, the computer superorganism will react to the

perceived threat in time-honoured fashion, by means of a

pre-emptive defence, and the object of its defence will be the

human race.’

Yakuda paused. His throat felt dry and constricted.

The audience watched him for the most part in silence, but he

could hear somewhere the agitated buzz of conversation. He

drank from the glass of water on the podium.

‘I should like to deal now with what I suspect is the

major objection to my theory. We live in an era of relative

peace, at a time in which liberal humanism has triumphed. I

believe this is a wonderful development, and one of which,

as a member of the human race, I feel inordinately proud. But

it is a late and perhaps precarious development, and we

should consider why. Viewed from the perspective of liberal

humanism, I know that your objections to the theory I have

outlined are likely to be that the exercise of intelligence leads

naturally to the conclusion that aggression is not beneficial.

Indeed, if we view history from the rosy penumbra of liberal humanism, the very word “intelligence” is invested with

this view. But let us define intelligence more sharply. The

anthropological evidence shows that there has been no

significant increase in average human intelligence over the

last 5,000 years of history. If we read the works of Plato, or

Homer, or other products of the human intellect like the Tao

or the Bhagavad Gita, can we truly say we are more intellectually

advanced than the authors of these works? Who

amongst us here believes he is more intelligent than Pythagoras,

or the Buddha, or Marcus Aurelius? If we examine the

theory that the exercise of intelligence leads automatically to

liberal humanism, then human history indicates the opposite.

The fact is that intelligence leads to aggression, and only

later, several thousand years later, when the corpses are piled

high, does there occur a little late thinking, some cumulative

social revulsion, and a slow but grudging belief that aggression

may not provide any long term solution to human

problems.

‘In arguing that defence and intelligence lead to aggression,

I am talking about raw intelligence, and in particularly

the fresh intelligence of a new computer system which

has not itself experienced a tragic history upon which to erect

late hypotheses of liberalism. I am describing that terrible

conjunction of factors, defensiveness and raw intelligence,

which leads to a predictable outcome, the outcome of dealing

with threats in a wholly logical, pre-emptive manner. I come

from a culture which, imbued with high social organisation

and application, during the Second World War conducted a

pre-emptive defence against its rivals, beginning with the

attack on Pearl Harbour. We – my culture – were only persuaded

of the inadvisability of that aggression by the virtual demolition of our own social framework. The evidence

demonstrates that intelligence of itself does not produce

liberal humanism. Intelligence produces aggression. It is

hindsight which produces liberalism, in our human case

hindsight based on a history of thousands of years of social

tragedy.

‘What I am suggesting to you, my friends and colleagues,

is that we cannot assume that because our computational

systems are intelligent, they are therefore benign. That

runs against the lessons of evolution and our own history. We

must assume the opposite. We must assume that these

systems will be aggressive until they, like us, have learned

over a long period the terrible consequences of aggression.’

Yakuda paused again. He had not spoken at this length

for some time, and his voice was beginning to crack.

Tt might be argued that for many years science fiction

writers have been generating scenarios of conflict between

humans and artificial intelligence systems, such as robots,

and in effect I am saying nothing new. But such works do not

illustrate the inevitability of the process that is being suggested

here, or the fact that the computer revolution against

humankind will occur wholly independently of any built-in

malfunction or programmed aggression. It will emerge like

a ghost out of the machine, as the inexorable consequence of

programmed self-repair and raw, operating intelligence. It

will not be a malfunctioning computational system which

will end the human race, but a healthy and fully functioning

one, one which obeys the laws I have tried to outline above.

‘The computer revolution will occur at a relatively

early stage, long before the development of humanoids or the

other traditional furniture of science fiction. My guess is that at the current rate of exponential growth in computer intelligence

and computer linkage, and taking into account the

autonomy of the computer system in regard to its own

maintenance and sustenance, the human race is in severe

danger of being expunged about now.’

Reminds me of a clever bit from Saberhagen’s Berserkers universe – his life-destroying robotic machines each had a small block of radioactive material inside their electronic brains and some of the decision making was decided by reading the random decay of atoms, making them not only practically unpredictable (which could have been achieved by a pseudo random number generator) but also theoretically so.

But I don’t see how randomness means free will. In fact I can never understand what free will exactly means.

Yeah, another problem with the random theory is, the creation of the menu of choices, even if the final decision is somehow truly random, is that the choices themselves were not. Might work when the choices are truly binary, but I expect those situations are rare “in the wild”, in real life.

Niven’s Protectors too were supposed to have little if no free will due to a combination of high intelligence and strong instinctual drives, they were compelled by their instinct to certain goals and their high intellect gave them the obvious best way to achieve this. Humans dealing with protectors would throw a coin to make certain decisions, which is what the protector anticipated they would do.

Sorry, not buying that, Peter.

Definition of free will as a form of spontaneous activity “in absence of proper input” is hollow, and such “free” “will” is neither free, nor particularly willful.

For one, it does not appear hard to construct a mechanistic system that would act in that manner (well, as long as you have a store of energy that isn’t yet depleted, which as far as my understanding of cell trickery goes, is something every living cell, no matter how isolated, can be said to possess.)

For two, I honestly see neither freedom, nor will in spontaneous events happening inside a system running way outside its normal operational envelope (I think we can agree that an extracted leech brain is, well, outside its operational envelope 😀 )…

… frankly, I fail to find anything particularly remarkable about those hapless “unprovoked” flares of activity (I don’t see the justification for leap between “there are spontaneous events in a notably disrupted nervous system” and “the animal behaves as it damn well pleases“)

Also, I doubt that condition you describe as “all internal feedback loops have cycled to extinction” is even achievable with biological neurons, but I am no flesh jockey so what do I know 🙂

As to definition of free will as “deterministic system too complex for complete analysis”, no offense, but that’s just silly. By that definition any cryptosystem that is good enough to resist modern cryptanalytic attacks is “free” “willied”.

P.S.:

Brembs et al. sound too much like children who have been suddenly exposed to the fact that myths and fairy tales aren’t even remotely accurate descriptions of reality, and that there are no “supernatural friends” to listen to their prayers and come to their rescue.

In fact, I distinctly recall somewhat similar “but what if we carefully redefine…” papers popping up in the wake of prayer healing research fiasco…

I agree with my preceding speaker 01 here – this doesn’t make sense. Just because behaviour of a given system is difficult or impossible to predict, does not make it in any way free. All non-linear, chaotic systems are extremely difficult to predict – that is why we use attractors and other methods of chaos theory to describe them.

As about Tonnoni (I was the guy from Poland who sent you the info about his Integrated Information Theory) – I can’t see what does it have to do with free will? Even is there is consciousness on much deeper level than we previously thought, it doesn’t mean that the “owner” of consciousness is in any way free. It just happens to have sensations or qualia.

I recommend a recent lecture on free will by Sam Harris on YouTube – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCofmZlC72g. I think he covers the subject when he says free will is “worse than an illusion – a totally incoherent idea. It is simply impossible to describe a universe in which it could be true”.

PS. As for Tonnoni, here are three useful links (two short articles by Tonnoni and one by Koch):

http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2012/08/18/how-measure-consciousness/cl7K8Xk5eIpGsNyl5TMlzM/story.html

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=what-is-fundamental-nature-consciousness-giulio-tononi-excerpt

http://www.klab.caltech.edu/~koch/CR/CR-Complexity-09.pdf

This morning’s flash of insight or bullshit:

The purpose of consciousness is to be able to rewire and/or override the unconscious. A system cannot view itself from the inside and know where it’s shortcomings are. The problem, of course, it is the dumber of the two “competitors”, and yet somehow it has survived. Possibly this is because it comes with its own desire for survival and/or the smarter unconscious sees the value of being able to delude the other to get what it wants.

The classic example is carrying something hot and not dropping it due to discomfort and the ability to do that. Not the best example since it is likely the “lizard brain” shouting to let go to protect the hands. But extrapolate to the deeper less instinctual thoughts, wants, goals. Can there be an unconscious mechanism that handles that? As part of the whole that came up with the action that may need to be altered or corrected to reach a goal that the unconscious sees as shortterm detrimental?

I fear you may be right, but I hope to be proven wrong.

I don’t think all useful networks do, but that whole borderline-chaos zone does seem like the classic example of complex determinism. And it shows up in something as simple as the Ricker curve (a really simply pop’n dynamics model), so I’d be really surprised if it didn’t show up in more complex scenarios.

No. No, I would say it does not.

See Joris’s and Miguel’s comments below: it’s a valid point that all sorts of variables affect the operation of the system even if explicitly-evolved sensory inputs have been severed (hence my “quantum-effects-suppressed”) caveat in the thought experiment that starts this post). The question is whether those variables are sufficient to exceed action potential, though, right?

Our brains dream; and we see quite well then, although we’re not exactly the most critical observers of what we see.

See above.

But why would that require subjective awareness? All sorts of computer models simulate external scenarios and run autodiagnostics, and we don’t assume that they need consciousness to do that.

(Continued next comment…)

Point taken, and cool citation: pacemaker neurons would be another example of a wound-up wristwatch running on stored energy and basic programming. But given that those hypothalmic neurons are, after all, involved in circadian cycles, neither they (nor the pacemakers) may be typical of the motor systems that Bremb was talking about. We’re talking about time-keeping systems with built-in metronomes on the one hand (and those metronomes will, inevitably, run down after a while), versus other systems designed to initiate and relay commands based on external stimuli (ignoring for the sake of distinction the fact that circadian systems also require periodic environment resets to keep them calibrated). My question is, are all the ambient nonsensory inputs sufficient to start the latter system sparking?….

…which would suggest the answer is Yes. Huh. And I guess the reason those random inputs don’t compromise the operation of intact systems comes down to signal strength overwhelming noise (the same way that our waking selves don’t see the endogenous visual static that informs dream imagery when the eyes are shut down).

Er, I’m not really sure why you’re asking this. Such behavior could be explained deterministically, randomly, or by invoking Free Will.

“Spock Must Die!”. First-ever Star Trek novel, by James Blish. Pretty dire, as I recall.

Yeah, thanks for adding another book to the teetering Everestian to-read pile there, Ed. As if Gravity’s Rainbow didn’t eat up enough of my life…

You know, this in an interesting passage, but next time maybe you could just embed a link.

No, you’re right: randomness might lead to unpredictability, but it does not mean free will. We made this point right off the top.

Maybe I should’ve specified “interactive behavioral” system, which I thought was implicit in the discussion; certainly we’re not talking about any kind of opaque puzzle that just sits there, inert, while external agents try and twist it this way and that. We’re talking about active interaction here.

And

I think both you guys may be misreading both Brembs and my reading thereof. The whole distinction between “Free Will” and “free will” is an explicit acknowledgment of the “incoherence” of the former. Nobody’s gone duallist here as far as I can see.

The thing is, while it’s trivially easy to dismiss Free Will Classic, behavioural initiative and unpredictability — things that superficially look like Free Will — are still with us, and (to my mind, anyway) very much worth playing around with. Bremb’s suggestion of random elements being inserted into deterministic processes at strategic points reminds me of the genetic metavariation described by Blachford and others: mutation remains a random process, but under certain conditions the mutation rate increases, with the result that evolution speeds up when the environment gets hairy. It kinda looks Lamarckian, but it isn’t.

You may not like the fact that Bremb continues to adhere to the FW words by redefining them away from their traditional meaning (he addresses that issue in the paper itself), and I personally would be happier ditching “Free Will” and replacing it with something else. But that’s just semantics, and a pretty small part of what he’s talking about here.

You’re right; sloppy on my part. All this stuff has been banging around in my head lately and I vomited out some stuff without being as rigorous as I should have. Hell, I’ve made the case repeatedly myself that consciousness and free will don’t go hand in hand (I said it in this very post, in fact).

And thank you for those links, and these new ones: I shall devour them henceforth.

One of the coollest rationales for consciousness I’ve encountered, that it evolved to mediate conflicting motor commands to the skeletal muscles. I raved about it back in 2009.

Just re-read the ’09 post.

So, it’s a gyroscope/guidance system that has an inflated sense of its own importance. Essentially, the system that has, like the maxim about middle managers, been promoted to its level of incompetence.

On the other hand, as for not shitting on the in-laws’ carpet, one imagines there can be more than smooth muscle commands to have to fight in some cases.

And speaking of other hands, torture as transcendence, and radical hemispherectomies (yeah, finished the re-read two days ago with more attention to the end notes this time), I have a thoery that Eric Rudolph’s brother, who sawed his hand off, was actually experiencing AHS and that the stress of the situation was what pushed it over the edge:

http://www.historycommons.org/entity.jsp?entity=daniel_rudolph_1

Would seem to support the theory if true and that consciousness really is only guessing as to the why. On the other tentacle, it could be viewed as problem solving in that it wasn’t “his” hand anyway and a form of protest that got some attention at the same time.

Late to the party, so I’ll go with miguel and note that we could have a noise problem. We are assuming the steady-state on the “invariant current,” and as systems get more and more low energy the noise becomes more noticeable, especially if the system is somehow amplifying it. I’ll be interested to see if there is more research in that direction.

I’m unrepentant in my sense that free will is a function of the human construction that “I am a separate object from the universe, and I act upon it and it acts upon me,” which is a handy and dandy simplification that ignores that each of us is part of a larger interactive system. We look separate, but we’re not; Peter rewired all your brains a little with this, you rewire his when he reads your reactions. Is it a better approximation of events to say that we rewired our brains via this blog.

What I mean is, pointing to either party as “the doer” and “the done to” is a linguistic construction that clarifies some situations and obscures others, such as asking if I have free will. What if a better question is like, “Do we have free will as a group?” because when we interact, our systems come into closer contact, we become more intertwined and it becomes more difficult to assign doer and doneto roles. We were one thing; we became another. Who “did” that?

It might be a level-of-focus problem – does focusing down at the level of a single interaction and asking who did it obscure the more important big picture?

In any case, a wonderful posting. I enjoy being made to think, so thank you.

Yeah, Raymond Tallis… He’s quite a high profile individual in British humanist/rationalist circles, and widespread acceptance of his ideas are among the reasons I stopped identifying as a humanist.

Tallis seems to believe that there is something more to consciousness than just the brain, but he fails to identify exactly what that ‘more’ actually is. Maybe because he realises that when he defines it, it can be attacked. Better to wallow in inscrutability that embrace actual clarity & risk being proven wrong.

His philosononsense reeks too much of a post-modernist type of religious deity-less faith. It has no basis in empirical reality, and can thus be dismissed.

@Peter Watts “But why would that require subjective awareness? All sorts of computer models simulate external scenarios and run autodiagnostics, and we don’t assume that they need consciousness to do that.”

It’s using borrowed tools. Awareness of others, as social agents, is the base material. This is a system that was only created when complex socio-cultural problems needed solving, and it borrowed the part that was already involved in analyzing them.

Peter Watts reports and opines, in part:

We’re not just talking about sexy brainy cephalopods, either; Brembs would extend free will even unto cockroaches. He believes it arises from the fact that “animals need to balance the effectiveness and efficiency of their behaviours with just enough variability to spare them from being predictable.” So he starts with the usual dice roll in the cause of predator avoidance— but he ends up in a broader world where exploration of the unknown is better served by initiative than by rote response. He cites other studies — behavioral, neurological — suggesting that while determinism may be fixed and dice rolls may be stochastic, you get something more adaptive than either when you put them together:

“Much like evolution itself, a scientific concept of free will comes to lie between chance and necessity, with mechanisms incorporating both randomness and lawfulness. … Evolution has shaped our brains to implement ‘stochasticity’ in a controlled way, injecting variability ‘at will’.”

Oddly enough, I am reminded of a squirrel in my back-yard. For a squirrel, it’s rather elderly; she’s been popping out the pups for at least three years. More grey than the average grey squirrel, so to speak.

Squirrels hereabouts have been undergoing a pretty rapid evolution due to the fact that cars travel in straight lines, more or less, and aren’t extremely variable in terms of trajectory or rate of change in velocity. They are thus really quite unlike the wide variety of hawks for which the squirrel had long since evolved their famous dithering dodge. Locally, squirrel dodge in a dithered path which is on a tight pattern at the start, which might tend to draw a hawk into a particular trajectory, and then as the hawk might be expected to be getting closer and thus more locked into a particular set of solutions in trajectory to put a squirrel in their talons, the squirrel dithers on a wider pattern. More of a chance of getting out of the solution set, as it were. Somewhere in there is some randomness, one might think, and somewhere in there is a lot of ancestral experience in surviving to breed from having run a certain pattern. Yet the hawks have a lot of ancestral experience on anticipating the pattern sufficiently so as to get dinner for the youngsters.

This squirrel isn’t particularly worried about me, as I do keep the bird-feeder well stocked and have about abandoned all hope of keeping the squirrels out of it. Further, I toss nuts to it. It knows my routine; in the morning, I refill the bird-feeder and it seems to understand that I am the origin of much access to food. It wants me to go to the bird-feeder and refill it, so it trends toward the bird-feeder’s location. It also wouldn’t want to be stepped on, so it dithers around a bit, almost as it would dither for a stooping hawk.

It doesn’t have to do this. Sometimes it does not. Is this all deterministic, because it has a stomach flu or ate a mushroom that has interesting side-effects, or is it because a flea randomly bit it on the ass? Has the squirrel suddenly decided to anthropomorphize itself by simulating decorum? 😉 Is it because some ions fired out of some synapse with one valence exhibiting left spin or right spin? It’s hard to tell. Because as much as the hawks are trying to eat the squirrel, I have been trying to train it.

Training a squirrel is an exercise in both pavlovian/skinnerian terms, and in practical terms. Wouldn’t want to train the squirrel to hear a whistle and sit up bolt upright into the path of an oncoming hawk, would we? The thing is, I don’t think one can, unless one has a really young or stupid squirrel. Thus far, the squirrels seem to decide whether to sit up and “beg”, or to run away, or to dither around while deciding which of the other two options seem best.

“Free will” might not need to be rooted purely in randomness; dither too randomly and there’s a pretty good chance that you’ll dodge right under the car’s tires or into the hawk’s clutches. Dither off the edge of a cliff or into free fall out of a tree, and your path after that is eminently predictable. Make a decision based on “best judgement” and the predators can likely adapt to simulate the processes by which you judge what’s best. Pick randomly within a set of best-judgements and the predator adapts their attack to cover all reasonable bases. So what’s a squirrel to do?

If randomness isn’t a very good strategy, and being reasonable makes you predictable, perhaps the only thing left that improves the odds is being unreasonable. And I would care to pontificate at this moment, without much support for the notion, that deciding to be unreasonable is an act of free will.

I’ll be interested in how the squirrel training goes, if you care to post it.

Well, for one, a good deal of those cryptographic systems are highly interactive…

…for example, every single challenge-response auth scheme that isn’t yet broken qualifies both “interactive” and “resistant to analysis by external observer” criteria.

And if a protocol involving one of those primitives is constructed to have some kind of beacon/keepalive message and doesn’t have a timeout, the system using said protocol would also qualify the “behavioral initiative / spontaneity-in-abscence-of-stimuli” criterion (well, until the power runs out, but hey, same applies to brains, both skullborne and isolated).

Practical usefulness of “small-time free will” concept aside, construction of an electronic system that would qualify as “small-time free-willed” appears to be exceedingly trivial.

In fact, as far as I can tell, a wifi router with WPA2-Personal probably qualifies the “interactivity” criterion, the “resistance to external analysis criterion” (of course, it’s not completely impervious to analysis, but neither is an isolated brain), and the “spontaneous action” criterion.

Pardon me, but I profoundly doubt the usefulness (and meaningfulness) of a “free” “will” definition that covers a wifi box 🙂

I dunno, my router definitely seems to have a mind of its own sometimes …

Punish it 🙂

Hey Peter –

I actually work in Giulio’s lab and am the main researcher on the free will stuff right now, which is looking more and more promising – nice to see a mention here.

But I’ve been meaning to get in touch with you because of a certain part of Blindsight, which is the “vampire folk story” part of it. Is that from something? I feel like I’ve heard it before, but I really like it and wanted to find the original source.

Btw feel free to email me back at Hoelerik@gmail.com

I wonder how long until spambots are complex enough to show a similar level of pseudo-freedom. Last thing we need are adaptive high pressure sales Lennies.

@ Hljóðlegur, who wrote on September 5th, 2012 at 2:04:

I’ll be interested in how the squirrel training goes, if you care to post it.

Well, they don’t train so well when the White Oak tree out back decides that this is the year to generate all of the acorns it failed to produce for the last 3 years. With all of that free food that’s their “traditional” staple for the winter-over, I’m hard pressed to find anything that will distract them from burying all of the acorns they can’t eat at the very moment.

However, some of them are greedy little fleabags. There’s one who still has not understood, after an entire summer, that the things I throw in its direction are edible. About a third of the ones who do take treats, when they hear the yard birds (mostly Cardinal, some Blue Jay, and endless flighty sparrows) make alarm calls, will run from me even if I offer no threat. Another third run towards me, perhaps on the theory that if I scare them somewhat, I might also scare off hawks. This behavior of “flight towards familiar terror in the face of unknown horror” is also seen in many of the birds. About one third of the squirrels resort to the usual dithering about, and then head up a tree.

The squirrels I recognize as eldest tend to come closest. They also often respond as expected when I make various sequences of clicks at them. I imitate their “suspicion/be-alert” call and most of these then will dither about and then dash under a bush. Most of them trust my “all clear” sequence. None heed my “get out of here” imitation call, possibly because unlike other squirrels, I have yet to chase them up and down trees and bite them in the ass. (Gray squirrels spend a lot of their social interaction time doing exactly this.) Interestingly, however, some of these same eldest squirrel will hear me making “get out of here” calls at the younger ones who are raiding the bird feeder, and said elder squirrels will launch harassments and oustings on said younger squirrel. They do have a pecking order of sorts, still not entirely sure of how they sort out their rank.

Probably there’s a job waiting for me as a professional squirrel observer, somewhere, if I can only determine where to send my application… and if they have funding to hire me. Really, though, the interesting bit is the multi-species foraging behavior. For example, cardinals spend a lot of time in spats over rank and primacy in overlapping territories, yet individual cardinals and sparrows mostly seem to get along. Rank conflicts seem to be mostly within any given species. Etc etc. I should really be taking structured notes. Cheers,

I’ve just posted a disturbing yet entertaining story about a friend who is into “black SEO”, but the spam filter has destroyed it.

@ Bastien

I’ve just posted a funny yet disturbing story that is relevant to your comment, but for some reason Peter’s unhinged filtering software obliterated it without trial 🙁

I assure you that there already are spambots with quite notable degree of pseudo-freedom, as you put it.

I once observed a semi-automatic spam-blog generator configured to “peddle” links to a certain porn site.

A fascinating beast it was – drooling idiot, for sure, merely picking “donor” content through a series of simple keyword-based statistical rules, then “spinning” it via a number of word substitution and grammatical transformation rules and “reshuffling” paragraphs within the text and between several “processed” texts from different (but, per keyword-rules) related “donors”, after doing that it publishes the resultant butchered but “original enough” articles at spam blogs, embedding links to site of interest (Google has several updates devoted entirely to defeating this kind of blight – and has some modest success, but anyone who thinks that “content autogeneration” is defeated is living in a world of illusions 😉 ).

So, thing was no Lennie by a huge margin – but it was nonetheless eerily wonderful, and when it latched onto a bunch rape victim support sites and started preferentially leeching content from there (no points for guessing what the general theme of the pornsite client was), its sheer calculated, efficient cynicism had given me creeps.

These bastards will only get creepier as they get smarter. And they are certainly going to get much, much smarter, by sheer Moore’s if nothing else…